With global sales in excess of $2.7bn in 2021, Parmesan is a cheese loved throughout the world.

Indeed, so steeped in tradition and so valuable is the cheese, that some banks in Italy accept it as collateral.

But given its status as one of the “oldest, richest cheeses in the world”, according to the Parmigiano Reggiano Consortium that oversees its production, Parmesan is also one of the most copied – with global sales of counterfeit cheeses valued at $2bn last year.

Made in a small area of northern Italy – in the provinces of Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena, and parts of Mantua and Bologna – the cheese has undergone very little change to its production process and is essentially still made in the same way it was almost 1,000 years ago.

So, what makes Parmesan so special and worthy of copying? And what is the consortium doing to protect it?

Benedictine monks in Emilia-Romagna first created Parmesan to extend the shelf life of the vast quantities of milk they produced some 900 years ago.

Made with only three ingredients – milk, salt, and rennet – it therefore contains no additives, only natural bacteria. And to create its distinctive taste, dairy cattle follow a specific diet.

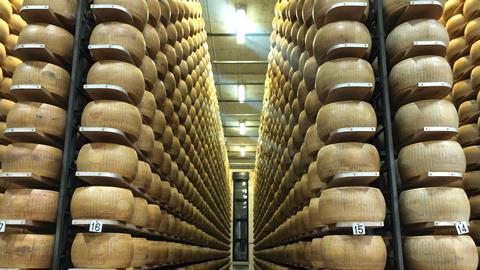

Parmesan also has a minimum maturation period of one year, but it can also mature for much longer, sometimes even years.

The San Bernardino dairy is one of 300 consortium approved dairies centred near Parma and has been part of the cheese’s tradition since the 1800s. It produces on average 15,000 wheels of Parmigiano Reggiano cheese per year, sourced from about 975,000 litres of milk per year.

And the dairy and Parmesan production are such core parts of the life of the community that it even has a chapel on site once used by the dairymen who lived and worked there.

But in recent years the consortium’s hold on this cheese has come under threat from copycats that are laying claim to its unique provenance.

Copycat threat

After a landmark case in 2008, in which Germany failed to argue that Parmesan was a generic term for any hard grated cheese, nothing in the EU can be called Parmesan if it is not the exact product, as part of its Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) status.

However, this rule does not extend to the US and China, where Parmesan fraud is rife – and not just as passing off one cheese as another.

In 2016, Time magazine revealed some American producers even made ‘Parmesan’ containing cellulose and wood pulp as filler. And the battle to protect the cheese’s identity continues, with big producers like Kraft in the US using the Parmesan name without proper approval.

Now the consortium is taking a particularly technological approach to protecting the product with a trial of 100,000 wheels of cheese having digital labels inserted into the casein skin.

The move is designed to improve traceability, inventory tracking and control, product authentication and quality assurance testing, plus product serialisation and consumer safety, it says.

“By integrating p-chip micro transponders into casein tags, the consortium can better control its inventory and protect and differentiate its products against look and sound-alike brands and have access to unmatchable track-and-trace technology to protect itself in the case of recalls or other issues,” it adds.

And if the trial is successful, the chips will be rolled out more widely.

This tech rollout was designed to “convey the value of our product globally and distinguish it from similar-sounding products on the market that do not meet our strict requirements for production and area of origin”, said consortium president Nicola Bertinelli, when the trial was launched earlier this year.

So, what makes Parmesan so special and worthy of copying?

As a protected product, Parmigiano Reggiano must comply with specific rules and regulations around its production. At a primary level, it must only be made with milk, natural calf rennet (not synthetic as used by big producers) and salt. The milk must come from local cows and the cheese must be produced in the Emilia-Romagna region.

There are also rules on how the cows must be treated and fed. While animal rights activists have in the past expressed concern about the lack of green space for the cows producing milk for Parmesan, this all comes back to regulations around what they eat. Namely, 70% of their diet must be locally sourced hay and the other 30% soy, barley and corn, not silage as is common in dairy cattle as it increases the quantity but decreases the quality, says Giovanna Rosati, consortium spokeswoman.

Each cheese is stamped for traceability

The vats are heated using steam through the lining rather than traditionally over fires

The Caseificio San Bernadino

Specialist diet

Were the cows allowed to freely roam, there would be no control over what they are eating, she adds.

The key difference with Parmesan compared with other hard cheeses is that much of what makes it unique comes from three key lactic populations, which the cows consume through the local hay.

A lot of the production process is designed to preserve these populations. For example, getting the milk to the dairy within a couple of hours, only heating the milk to the cow’s body temperature and allowing it time in moulds before salting to make it more acidic. Crucially, the three lactic populations also create the signature crunch of the cheese as they metabolise the proteins over the maturation period, which also makes it, according to the consortium, a healthy product as the protein is preserved.

When the cheeses are quality checked at the 12-month mark, the quality checkers are looking for defects – holes both big and small created by fermentation not done by the three lactic populations. Quality assurance has nothing to do with food safety, but is to check each cheese can qualify as Parmesan.

There are three levels of quality assurance. The top ranking are perfect cheeses which must mature for at least another year to become Parmesan. Then there are the cheeses with small defects which are no longer worth maturing and are sold as 12 month matured Parmesan and finally those which don’t pass quality assurance checksand are sold as generic cheese to big food producers.

Parmesan is described as the “perfect example of PDO” as it is not a result of a patented recipe. It is made of three components, Rosati says: “The soil from which the hay is grown, the climate which enables the hay production three times a year and the human factor with tradition and skills.”

Tradition is inherent but the dairies, typically co-operatives owned by multiple producers, have had to move with the times. They have invested in new technology such as a cage to hold the cheese in brine for salting. A robot, meanwhile, picks up each individual wheel of cheese during maturation. It cleans it, turns it over and puts it back on the shelves to ensure even distribution and cleanliness.

Most preparation continues to be done by hand, which has its benefits beyond just product quality. As energy costs across the world soar, Parmesan dairies are relatively protected as production has a “very limited use of energy”.

During quality assurance each cheese is checked using a hammer to hear for vibrations showing defects

The only two cheeses which are the same are the ones which come from the same vat

Climate challenge

However, while the tradition continues, the soil and the climate are increasingly under threat from global warming and climate change.

This summer, which was notably dry across Europe, caused a “huge problem” in hay production. And due to the regulations on cattle diets, Parmesan producers “have no plan B,” says Rosati. “How do they get the three lactic populations otherwise and in the right quantity?”

And this is a situation that is likely to get worse. Rosati points to a study in Canada that showed higher winter temperatures were affecting the bacterial population of the local soil, which had a knock-on effect on hay. “If it has affected hay in Canada, chances are it is going to do the same here,” she says.

Parmesan production is seen as an art form for those in Emilia-Romagna. However, talent is not the only thing keeping Parmesan alive, and with the threats of climate change and fraud looming, producers will have to continue to adapt to keep the famous cheese alive.

No comments yet