It took a Manchester United footballer to force the government to extend free school meals during the pandemic. The food industry has been just as eager to help – but how much can it change by itself?

This article is part of The Goodness Issue, a special edition of The Grocer dedicated to celebrating the work the grocery industry has done to tackle environmental, political and humanitarian issues facing the world today

Read more: What the supermarkets are doing to tackle food poverty

A year ago this week, industry leaders were fuming over the lack of government planning to help them cope with the looming pandemic, as its deadly and disruptive consequences became all too clear across Asia and Europe.

Yet the warning, almost a month to the day before Britain was plunged into the first lockdown, appeared to fall on deaf ears. The lack of major shortages on the supermarket shelves was largely down to heroic efforts by the industry and the supply chain, rather than government intervention.

But beyond that short-term disruption, another catastrophic impact has emerged: a wave of poverty that has thrown childhood hunger into the spotlight.

The government response to that has faced accusations of being equally shambolic. Campaigners are warning that, far from nearing the end, we are just beginning the battle to prevent the nation’s children going hungry due to the economic impact of Covid.

So what is the industry doing to help? And what support does it need from government?

Earlier this month, Food Foundation CEO Anna Taylor revealed to the all-party environment, food and rural affairs committee (Efra) results from a major survey, which found a shocking 12% of households with children had experienced food insecurity during lockdown. More than one in 10 had visited a food bank.

Faced with such frightening figures, ministers have been accused of, as one source describes it, “serial dithering”. A report by the same committee in October slammed the government for its “lack of urgency” in tackling food insecurity, while many believe a certain Manchester United football star has done far more to prompt action than anyone in Westminster.

How the pandemic has accelerated food poverty

1.2 million

food parcels distributed in first six months of pandemic

470,000

of the 1.2 million parcels go to children

47%

year-on-year increase in demand for food banks

74%

increase in demand across five years prior to pandemic

Source: Trussell Trust

In June, Marcus Rashford successfully campaigned on the issue to force a government U-turn to extend free school meals into last summer’s holidays. On the back of that victory, the footballer launched a child food poverty taskforce in September, involving a raft of supermarkets and suppliers ranging from Aldi to Waitrose, alongside FareShare and the Food Foundation.

Their work began immediately. As well as promising to use their respective social media platforms to share stories of those most affected by child food insecurity, the taskforce urged Boris Johnson to implement key proposals from the National Food Strategy (NFS), published in July by Leon restaurant founder Henry Dimbleby.

It called for the expansion of free school meals to every child from a household on Universal Credit, extending holiday provision to support all children on free school meals and increasing the value of the Healthy Start vouchers from £3.10 to £4.25 per week. Dimbleby himself has been outspoken in his criticism of the government, which he claimed was “not doing enough” to tackle child food poverty.

The unilateral pressure worked. Just like his U-turn on school meals last summer, Johnson was back on the phone to Rashford in November with another, at least partial, climbdown.

Although some key elements of the NFS were ignored, he did offer a new £400m package of support. That included giving £170m to local councils to fight hunger and allocating a £16m grant to the nation’s food banks, alongside a boost to the Healthy Start scheme.

Healthy Start is a prime example of the need for industry efforts to be underpinned by government action. Since their launch in 2006, the vouchers have suffered from a dire lack of take-up. As of December, only 269,000 out of 540,000 families eligible for the scheme were registered.

The government has now committed to bolstering the scheme from April, with a higher value for the vouchers and with a new app-based digital system, designed to breathe new life into the initiative. At the same time leading supermarkets have redoubled their efforts, and appeared in a race to outdo each other with pledges to top up the vouchers.

Read more: What the supermarkets are doing to tackle food poverty

Top-ups have come from the likes of Tesco (£1), Waitrose (£1.50), Co-op (£1) and Lidl (£1.15). Earlier this month, Sainsbury’s announced the biggest top-up yet of £2. Rebecca Tobi, project manager at the Food Foundation, who was been helping negotiate the top-ups on behalf of the taskforce, says supermarkets have “thrown their weight” behind the scheme.

However, her crucial point is this: to be truly successful, far more needs to be done to publicise the relaunch of Healthy Start and widen its uptake.

Campaigners warn without a major publicity drive, backed by government funding and full-scale marketing from supermarkets, many families will not come forward and awareness of the scheme will remain low.

And although the government has agreed to boost the value of the vouchers, Dimbleby’s proposals to extend them to all pregnant woman and households with children under four receiving Universal Credit have, laments Tobi, been met with a “wall of silence”.

It’s a similar story when it comes to free school meals. Ministers have been accused of ignoring “millions” of children at risk of hunger because of the pandemic, despite Rashford’s breakthroughs.

The NFS calls for the free school meal scheme to be available to every child up to the age of 16 from households where a parent or guardian is in receipt of Universal Credit. That would see an additional 1.5 million seven to 16-year-olds get free school meals.

The industry is keen to support these efforts. Last month, Co-op CEO Jo Whitfield joined dozens of hunger charities and education groups in writing to the PM to demand a wholesale review of the system.

But ultimately, the power lies in the hands of the government. And the estimated £670m price tag could prove a stumbling block. At the same time, research suggests if the government were to fully enlist the support of the industry in the battle to avoid child hunger, it could in the long term save sums for the economy that make the called-for expenditure on school meals look like peanuts.

What they say about child hunger

“Mothers and fathers are raising respectful, eloquent young men and women, who, in reality, are part of a system that will not allow them the opportunity to win and succeed. Add school closures, redundancies and furloughs into the equation and we have an issue that could negatively impact generations to come. It all starts with stability around access to food.”

Marcus Rashford, Manchester United footballer and hunger campaigner

“This problem is real… it’s serious, it’s immediate and it’s going to get worse as unemployment gets worse and the government isn’t doing enough.”

Henry Dimbleby, Leon restaurant founder and author of National Food Strategy

“Whilst some important measures have been put in place, they are not going far enough. What we are hearing directly from households with children is that the challenges are immense of order to put a healthy meal on the table.”

Anna Taylor, executive director, Food Foundation

“We have a minister for women, we have a minister for veterans. We have a minister for the disabled. We should have a minister for the hungry.”

Ian Wright, chief executive, FDF

“We are going to make sure that we have no kids, no pupils in our country who go hungry this winter, certainly not as a result of government inaction.”

Boris Johnson, prime minister

The economic case

That’s another area where the industry is looking to help by building a case. In January a study by Pro Bono Economics, in partnership with children’s charity Magic Breakfast and Heinz, claimed providing disadvantaged pupils completing key stage 1 with just one year’s supply of school breakfasts could generate long-term economic benefits in excess of £9,000 per child.

More than 90% of these benefits would come in the form of improved lifetime earnings for the beneficiaries, with the remainder due to reduced costs for special educational needs, truancy and exclusions, it found.

With an estimated 298,000 pupils aged between six and seven completing key stage 1 at schools with high levels of disadvantage, this figure amounts to a staggering £2.7bn in benefits across England alone.

“For the government to remove funding for breakfast clubs would be a huge step backwards”

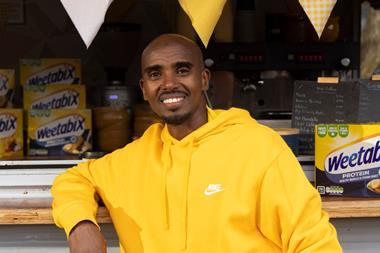

Heinz is one of a raft of food companies backing the charity, alongside the likes of Arla, Morrisons, Weetabix and Tropicana. Heinz No Added Sugar Beanz are currently being offered at 100 schools across the country as part of the Magic Breakfast provision, reaching over 101,000 children before schools closed in lockdown.

As that example highlights, lockdown has put a dent in overall progress. Before Covid, parliament was due to debate Labour MP Emma Lewell-Buck’s School Breakfast Bill, which would have extended and scaled up funding for such breakfast schemes. But the bill, supported by over 70 MPs, was postponed indefinitely due to the pandemic.

Supporters, including leading food companies, are now calling on the government to make a commitment in next week’s Budget to provide school breakfast funding to 8,700 schools in disadvantaged areas of England, and for it to become part of a long-term and sustainable strategy. “This is a critical moment in the fight against child hunger in the UK and for the government to remove funding for breakfast clubs would be a huge step backwards,” says Jojo de Noronha, president of northern Europe at Heinz.

Kellogg’s, which began supporting Magic Breakfast during Covid-19 by providing over 200,000 boxes of the new WK Kellogg’s for Kids cereal for schools and in-home delivery packs, has also written to the government to urge it to pass the bill.

Children Food Campaign director Barbara Crowther says the difficulty in pinning down government commitment over issues such as free school meals and breakfast clubs is typical of what has happened since the pandemic began.

“We’ve had various sticking plasters from the government, but it feels like it’s been a constant battle to get them to commit to longer-term action that will stop this sort of crisis happening again,” she says.

It’s a view shared by James Persad, head of marketing at FareShare. The redistribution charity has provided over three million meals a week to vulnerable people compared to under a million before the pandemic. Against that backdrop, he’s calling for a more co-ordinated approach to fund support for charities and food banks. Persad describes the “terrifying” situation going into the pandemic. “We simply didn’t know whether we would have enough food,” he says.

“An avalanche of support from the food industry” saved the day, he says. That also included a £10.5m grant from Defra. However, the long-term outlook is more worrying. FareShare has yet to succeed in getting the government to commit to annual funding of £5m for its Surplus with Purpose scheme, which helps towards the cost of suppliers distributing surplus food.

“We’ve had various sticking plasters from the government, but it feels like it’s been a constant battle to get them to commit to longer-term action”

The problems are also organisational in nature. One senior industry source says suppliers have been “bombarded with competing requests” from food charities because of a lack of government leadership and an established protocol. To tackle the issue, the FDF met with suppliers last week to discuss how support for redistribution charities could be made more joined up. CEO Ian Wright said it served to highlight the need for a minister to take overall control of the hunger crisis.

“Marcus Rashford has highlighted a problem but that’s about one-third of the market,” says Wright. “Of the total number of people who are served by donated food every day, the vast majority are adults, OAPs, lunch arrangements, the homeless, almost every refuge or shelter, refugees – all of these and many more are people who rely on donated food, and because of the situation with hospitality a lot of that stuff has dried up.

“This is why we need a minister for hunger. The government won’t accept it but someone has to be responsible for this,” he argues.

Yet it’s not just the government coming under pressure to step up its co-ordination. Mark Game, CEO of Manchester-based redistribution charity The Bread & Butter Thing, says the food and drink industry has also struggled due to industry red tape and “arcane” rules – something that needs to change if the response is to be more effective.

Game, who is also a founder member of new independent food redistribution network Xcess, claims thousands of tonnes of food is ending up as animal feed or going to anaerobic digestion because groups like those it represents cannot access much of the private-label food surplus from supermarkets.

“I don’t want to criticise anything that’s happened because there has been some astonishing work in response to this crisis,” says Game, formerly CEO of Company Shop, the UK’s biggest redistributor of food and household surplus products. But he adds: “There’s been a lot of snap decisions and a lot of people making decisions that are operating in their own ecosystems.

“When all the pubs and restaurants closed there was a tsunami of donations. It was genuinely chaos. The government was blindsided,” he says. “They didn’t know what to do and they didn’t have the right processes in place. But the industry also needs to step up. We need to look now to make sure it never happens again.”

Redistribution commitments

Unlike the calls made a year ago, these appeals do appear to be getting through to the industry’s most powerful players. And that’s resulting in some genuine progress and meaningful goals.

Last week, The Grocer revealed IGD and Wrap had launched a major initiative to ask food and drink companies to more than double the amount of food surplus going to redistribution in the next four years.

Mark Little, the director of health and sustainability programmes at IGD who is leading the programme, says the aim is to have greater consistency in approach as well as a dedicated online hub of information to share best practice. He knows the importance of that, having formerly been head of sustainability and food waste reduction at Tesco.

Granted, food surplus isn’t the entire answer. Food waste and child hunger campaigners will rightly point out much more needs to be done to tackle food insecurity at its roots. But the Wrap-IGD initiative surely bodes well and sends out another strong message to government.

While it may be right that public inquiries into the handling of the coronavirus crisis wait until lockdown is lifted, the lessons on how to prevent millions of children going hungry have to be learnt now – and embedded in policy to ensure disaster doesn’t strike again.

Could supermarket workers be at risk of food poverty?

In January, a report by the Living Wage Foundation claimed 45% of supermarket workers, no less than 410,000 employees, were earning below the ‘real living wage’. That’s £9.50 per hour outside London and £10.85 per hour inside London.

The figures also revealed the “pay gap” in the industry, claiming that supermarkets had some of the largest differences in pay between CEOs and their colleagues working on the shop floor.

Tesco, Morrisons and Ocado were among the top 10 FTSE 350 companies with the biggest gaps. Tesco had the largest of the supermarkets, and third largest in the overall ranking, with a pay ratio of 355:1 for CEO/lower-quartile employee ratios.

“Supermarket workers have been vital in keeping the country fed throughout this crisis, but nearly half find themselves paid less than the real living wage and unable to afford the basics,” said Laura Gardiner, director of the Living Wage Foundation.

“We’ve all been hit by this storm, but while supermarkets have weathered it and made record profits, thousands of their workers are struggling to keep their heads above water.

“It’s high time they were paid a real living wage so that they can put food on their tables, as well as ours,” she added.

Things are changing. On the day of the report, Morrisons had become the first supermarket to guarantee pay of at least £10 an hour. It said the move would mean a “significant” pay increase for nearly 96,000 Morrisons staff.

The following week Aldi raised its minimum hourly pay from £9.40 to £9.55 nationally and from £10.90 to £11.07 inside the M25, claiming the move made its staff the best-paid in the sector.

Barbara Crowther, director of the Children’s Food Campaign, says this work needs to continue. “The food industry needs to look at the policies that contribute towards poverty in the first place and that includes paying staff who work in supermarkets a living wage,” she says. “The number-one reason for food poverty is low income.”

No comments yet