Walmart’s catastrophic earnings downgrade last week – which wiped 10% from its market value on Wednesday – was a shock to Wall Street.

The US markets were taken aback by the announcement that heavy spending on staff and ramping up its online offer would cut its full-year earnings by 6-12% from next February.

But observers of the UK grocery sector may have been experiencing more than a hint of déjà vu as the Walmart story rehashed some now very familiar concepts.

The US and UK grocery markets are clearly different – notably discount and Dollar stores have always been a significant feature of food shopping across the Atlantic, while Aldi and Lidl have made hay in the discount vacuum in the UK.

But some of the key themes and challenges remain – most importantly that the old superstore models are coming under unprecedented pressures.

Walmart has traditionally driven sales growth through its sheer size and scale – using its dominant position (around 25% of the food retail sector) to drive incremental growth through building more and more space, while keeping pressure on rivals through low prices.

Expanding its massive store footprint has driven revenues to almost $500bn and secured its position as the largest retailer in the world.

But it also creates a problem, that in the long-term growth driven primarily by expansion at some point becomes unsustainable – especially when, as the UK grocers have found, your business is getting squeezed a whole host of different angles.

Much of the media has focussed on online – an Amazon v Walmart battle that Walmart is losing. True, Walmart has been slow to build an online offer – certainly far slower than its UK contemporaries – but online is just one of Walmart’s problems.

It is also finding itself – like UK retailers – seeing its price advantage being eroded by hard discounters such as Costco and soon to be joined on a large scale by Aldi and Lidl. Also it is having to redraw its strategy of focussing on big box superstores to try and cope with increased trend for convenience shopping in the US.

Bernstein analysts sum up the situation as: “Consumers across all income classes want Walmart’s vision of “seamless” integration of ecommerce and brick-and-mortar, but they aren’t willing to pay for it… Hence, margins will be down with hopes that EBIT dollars will grow from a faster topline.”

How to drive this fast topline? Walmart’s response is – once again mirroring the UK – to fire up a price war to try and reclaim its declining market share and support flagging like-for-like sales.

So the retailer has pledged to invest “several billions dollars” in price over the next three years to drive organic sales growth. While a big chunk of this will come from Walmart’s own pockets, the retailer is also expected to turn the screw on its suppliers to drive efficiencies – much like the squeeze suppliers have faced from UK retailers trying to prop up margins in recent times.

Bernstein argues: “We believe the pinch from Walmart on [the consumer goods sector] will undoubtedly happen over the next few years in terms of inventory, price investment, supply chain support, competing versus increased private label… which should impact the smaller players more than the larger ones, but all will be impacted.”

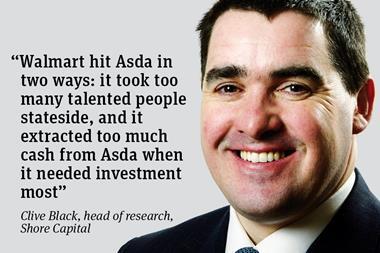

Interesting, Walmart’s approach to the changing US market is somewhat at odds to its own Asda chain in the UK – which has focussed resolutely on top-line profitability at the expense of throwing cash at supporting falling like for like sales.

Certainly its $1.5bn investment in employees, in terms of wages and staff numbers, doesn’t suggest a company in retreat and cutting back costs to support earnings. But what happens next depends entirely on how well Walmart’s renewed investment strategy is able to tackle some of the structural changes it is facing.

The UK retailers know very well that price cutting isn’t always a panacea for an outdated business model.

No comments yet