It’s time to get serious on transfats. Or so says the World Health Organization, which today launched a high-profile campaign calling for industrially produced transfats to be eliminated from global supply chains by 2030.

And with good reason. The WHO estimates transfat consumption is responsible for more than 500,000 deaths from cardiovascular disease every year, because they increase levels of the ‘bad’ LDL cholesterol in the body and decrease levels of ‘good’ HDL cholesterol.

It’s nasty stuff, and you don’t have to eat very much of it to put your health at risk. The WHO recommends total transfat intake should limited to less than 1% of your total energy intake, which translates to less than 2.2 g/day with a 2,000-calorie diet. Eating more than that, studies suggest, increases heart disease risk by 21% and deaths by 28%.

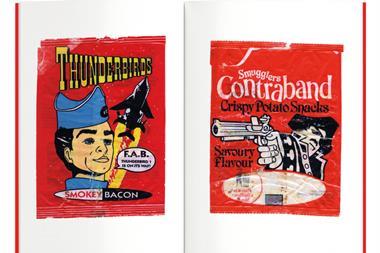

Industrially produced transfats were introduced into our diet through hydrogenated vegetable oils which, ironically, became increasingly popular from the 1950s to the 1970s as people looked for an alternative to butter amid fears over saturated fat. Because they are cheap and have a longer shelf life than other fats, hydrogenated vegetable oils soon found their way into an array of baked and fried foods, as well as margarines and spreads.

Things began to change in 2007, when the UK government – which has always resisted calls for a ban on transfats – published guidelines encouraging food manufacturers and retailers to voluntarily remove them from products. That same year, Britain’s major supermarkets promised to eliminate them from own label lines, with a broader commitment following in 2011, when 170 companies pledged to cut them from food products as part of the coalition government’s Public Health Responsibility Deal.

All the evidence suggests they’ve lived up to their promises. Until the 1980s, margarines contained 10%-20% transfats, while now they are virtually free of them, according to the British Dietetic Association. And a 2013 analysis by the Institute of Food Research and a division of the government’s Department of Health suggested that since 2007, concentrations of trans elaidic acid – the most predominant artificial transfat, had been slashed by 75% – from 0.8/100g to 0.2/100g.

It means that, according to the latest National Diet and Nutrition Survey, transfatty acids currently provide just 0.5%-0.7% of energy in the average UK diet today, which is well within the WHO’s recommended threshold.

Public health

And most of that comes from naturally occurring transfats in meat and dairy, rather than the artificial transfats found in things like pizza, buns, cakes and pastries, the survey suggests. Which is positive for public health, because according to the British Nutrition Foundation, “it is only trans fatty acids produced during the hardening of vegetable oils that are found to be harmful to health” while “the public health implications of consuming trans fatty acids from ruminant products are considered to be relatively limited”.

It was unsurprising, then, that the FDF responded to the WHO campaign by stressing artificial transfats have been “virtually eliminated” from UK supply chains through “voluntary action by food businesses”.

But public health experts believe the food industry – and the government – should go further. Simon Capewell, professor of public health and policy at the University of Liverpool, who has long called for a total ban on transfats, told the Telegraph that while the average UK intake is less than 1% of total energy, poorer people probably eat much more than that. “The public health community are in consensus that transfats should be eliminated,” he said.

By failing to take more concrete action, he argues, the UK is lagging behind countries like Denmark. Denmark restricted industrially produced transfat in all food products in 2004 has since seen cardiovascular disease death rates decrease by 3.2% more than in similar countries that did not implement restrictions.

Other European countries and the US and Canada have also implemented restrictions on transfats, alongside labelling requirements for packaged foods. And so have lots of other nations. In fact, when you start looking at the WHO’s long list of countries that have taken action on transfats, the UK’s lack of any regulatory action does look a bit odd.

Arguably, if artificial transfats have already been virtually eliminated from UK food supply chains, it wouldn’t be a huge step to ban them altogether and make sure they don’t creep back into our food.

Perhaps, with such damning evidence against transfats, this is one piece of red tape that should be embraced in post-Brexit Britain. After all, even one preventable death is too many.

No comments yet