This week an alliance of environmental, animal welfare and farming groups took up the mantle to answer the question of what ‘better’ meat and dairy looks like

How do we feed our appetite for meat and dairy without destroying the planet? It’s a question increasingly asked by shoppers and supermarkets, yet clear answers have been notable by their absence.

While a plethora of studies support the notion that consumption of beef, lamb and cheese must fall, there has been little consensus on how the remainder we continue to eat should be produced.

Until now, that is. This week, Eating Better, an alliance of environmental, animal welfare and farming groups including the WWF, RSPCA and LEAF, took up the mantle to answer the question of what ‘better’ meat and dairy looks like.

The group, which aims to halve meat and dairy consumption in the UK by 2030 and transition to “better production as standard”, has even published a ‘Sourcing Better’ guide for supermarkets. So what does it suggest? And how are grocers likely to respond?

The guide highlights eight environmental impacts of meat and dairy, such as greenhouse gas emissions, soil health and pollution and animal welfare, offering guidance on how supermarkets can change their sourcing to address each issue.

Simon Billing, Eating Better’s executive director, says he hopes it can help supermarkets set a “direction of travel” that places them at the vanguard of reform, by sourcing ‘better’ as standard and ultimately integrating the ‘best’ standards of production into their supply chains.

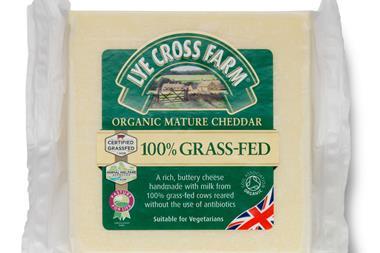

While supermarkets sourcing policies can often simply aim to meet minimum legal requirements or standards such as Red Tractor, says the report, they must expand to strive for ‘better’ standards such as RSPCA Assured and LEAF Marque. Eating Better also lays out the aspirational ‘best’ indicators and standards, such as organic, free-range and Pasture for Life.

For example, supermarkets can take direct action to address deteriorating soil health by sourcing only from farms using low animal stock densities and minimal chemical fertilisers, says the report. They could tackle greenhouse gas emissions by sourcing from producers engaged in agroforestry.

Billing admits that selling ‘less but better’ meat and dairy will require “a complete mindset change for the retailers”. One that could prove difficult given the current economic climate. Just last week, Sainsbury’s launched its ‘Aldi Price Match’ campaign, for example, which included price cuts on meat and dairy staples.

Food poverty

There is also the question of food poverty. Supermarkets have long been concerned that higher food costs could unfairly punish low-income households.

Several studies have suggested this could be mitigated through government subsidies and wage hikes. A Chatham House report this month said a mandatory fair wage, social safety nets for vulnerable households, and subsidies to support healthy and sustainable foods may be necessary to mitigate the risk of food insecurity through rising prices.

But while he acknowledges that government intervention is essential for food system reform, Billing dismisses the notion that retailers can wait for Whitehall to intervene. “We’re in a climate and nature emergency. I don’t think it’s time to wait, it’s time for leadership.”

Dan Crossley, executive director at the Food Ethics Council, agrees supermarkets must act now. “We have to experiment. Things might not be perfect, but we have to get on with it today rather than in a few years’ time.”

While supermarkets remain a “mixed bag” in their sourcing policies, they are in a position to lead the way and trigger a mindset shift that turns the focus from price wars to better quality for all shoppers, Crossley says.

“It should be a ‘race to the top’ rather than a ‘race to the bottom’,” he says. “Because inevitably, price wars lead to either cuts in quality or cuts in margin for farmers, which isn’t a sustainable model.”

No comments yet