A new US report suggests the majority of Amazon’s private-label brands fail to make an impact with shoppers. But does this hold true for UK grocery?

‘Most Amazon brands are duds, not disruptors.’

So declared a Bloomberg headline last week, following the publication of new research into Amazon’s own-label range.

E-commerce research firm Marketplace Pulse examined 23,000 Amazon own-label products on sale in the US and assessed their market impact based on category sales rank and customer reviews.

It concluded that though Amazon has lots of advantages over rival brands – including granular shopper data, its Vine review programme and the ability to prioritise its own brands in search results – these advantages don’t typically result in better cut-through with shoppers.

“The popular narrative has been that by utilising internal data, Amazon can launch its brands in many categories and capture most of the category’s sales,” Marketplace Pulse said in its report. “So far there is no evidence of this working.”

But do these findings reflect the impact Amazon own label is having on UK grocery?

First: some context

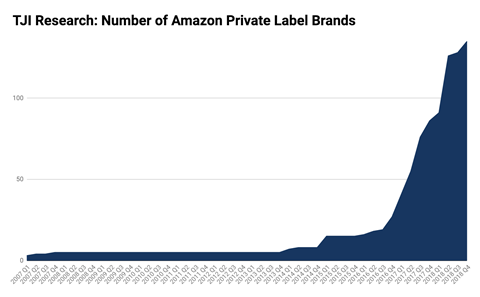

Amazon has expanded its own-label range at an aggressive pace over the past couple of years.

Since the start of 2017, its number of own brands has grown from 27 to 138, according to research by TJI, another e-commerce research firm. Its range now includes private-label milk (US-only at this stage) as well as new skincare, cosmetics and vitamins lines.

TJI doesn’t break out UK-specific figures, but it’s fair to say the UK reflects the global trend.

Own-label grocery brands on sale through Amazon UK now include:

- Solimo (includes coffee, chocolate and razors)

- Happy Belly (nuts, dried fruit and coffee)

- Wickedly Prime (pasta, pesto, olive oils and vinegar)

- Amfit Nutrition (sports nutrition)

- Presto! (household and paper products)

- Mama Bear (nappies and baby wipes)

- Lifelong Complete (petfood)

Plus, there’s a slew of lines from Whole Foods Market that became part of the Amazon own-label universe following its takeover in 2017.

Exclusive brands

At the same time, Amazon has been ramping up its range of Amazon-exclusive brands.

According to TJI’s database of Amazon products, the online retailer currently has 427 exclusive brands on sale globally.

Exclusive brands can be tricky to identify, as they don’t tend to carry Amazon branding or are flagged as Amazon brands in search results. (TJI’s methodolgy involves searching trademark records to verify brand ownership.)

Impact in grocery

The Marketplace Pulse study examined both own-label and Amazon-exclusive brands, across all categories, and found:

- own labels for generic items using the Amazon name (eg AmazonBasics batteries) work well

- otherwise Amazon own brands “are not resonating with customers”

“Amazon’s private-label efforts have been given too much credit, both in their ability to disrupt categories and the capability to utilise internal data.”

However, this doesn’t mean UK fmcg brands and rival grocery retailers should breathe a sigh of relief.

Own label is much more established in grocery than in other categories, the author of the study, Joe Kaziukenas, points out.

Amazon’s own-label brands are therefore having a bigger impact in grocery than Marketplace Pulse’s headline findings suggest.

There may be ‘duds’ in other categories, but “Mama Bear, Presto and Solimo in grocery are top-performing brands” says Kaziukenas.

In a market like the UK, where own label has a much larger share of grocery than in the US, the impact of Amazon’s own-label brands could be bigger still.

Category success

This is particularly true of categories that involve bulky items (such as nappies or paper towels), regular replenishment (such as razors) or where shoppers are already used to shopping online.

Coffee pods are a good example of the latter and have been a focal point for Amazon’s own-label strategy in the UK for some time.

Industry sources also point to petfood as a category where Amazon has managed to build up a sizeable and disruptive own-label business.

From Prime to Pantry

Another sign of Amazon’s growing confidence around own-label grocery in the UK is that it is making more of its own brands available as single items through Amazon Pantry.

Previously, its own-label lines had been primarily bulk purchases, especially in categories targeted at hotels, cafés and restaurants.

Now Amazon brand items available through Pantry include individual 190g jars of Wickedly Prime pesto and single bottles of Presto fabric conditioner.

Of course, none of this is unusual in and of itself.

As tech commentator and Andreessen Horowitz partner Benedict Evans remarks in his latest newsletter: ’It baffles me that people talk about Amazon’s brands as though retailers haven’t been doing exactly the same thing for a century.’

But Amazon isn’t just any retailer.

It is already facing growing scrutiny over its dual role as marketplace operator and competitor.

Recently, Elizabeth Warren, an influential US senator, launched a campaign to break up tech giants such as Amazon because of their ability to ‘tilt the playing field’ in their favour.

All this means the Marketplace Pulse study comes at a critical time for Amazon.

After all, it appears to show Amazon is not managing to tilt the playing field quite as dramatically as critics like Warren would suggest.

However, what may be true for Amazon own label in general does not necessarily apply to Amazon own label in grocery – and UK grocery in particular.

Despite the headlines about ‘duds’ and non-disruptors, fmcg brands and rival retailers have every reason to stay on their guard.

Julia frequently appears on radio and TV as a commentator on grocery retail and the politics of food and food sourcing, and has worked extensively on food authenticity and fraud issues. In 2013, she headed up The Grocer’s coverage of the horsemeat scandal.

Prior to joining The Grocer in 2010, Julia was editor of New Media Markets, a trade publication for the TV industry. She started her career as a staff writer for The Legal 500 at publisher Legalease. @juliaglotzView full Profile

No comments yet