It’s not just that Scotland is going it alone. Retailers and suppliers are at loggerheads with government – and each other – over the timing, the potential inclusion of glass, the potential for fraud, the cost and the unintended consequences. So what’s going on?

Relying on harmony and collaboration between England and Scotland is always a dangerous game. And amid the chaos of Brexit, there are growing fears DRS could become a recipe for cross-border chaos, rather than a cure for pollution.

Seldom have three letters – short for (bottle) deposit return scheme – been the source of such controversy, disagreement and at the same time high expectations.

But with both governments making DRS their main frontline weapon in the war on plastic, is there any chance of this becoming a coherent strategy?

Depite many clashes on how DRS should work, retail bosses, drinks companies and environmental campaigners alike have generally agreed on one thing – the need for a joined-up solution that works effectively across the whole of the UK.

As things stand, that looks as distant as an outbreak of peace and harmony on Europe. Instead, Scotland, which was the first to formally propose a DRS in 2017, is seemingly steamrollering ahead with DRS while Westminster, as Iceland boss Richard Walker aptly puts it, appears to have “kicked the can far down the road”.

The Scots latest landmark move came earlier this month when it released draft legislation to pave the way for the rollout of DRS in the country from April 2021.

Nicola Sturgeon’s blueprint would see a 20p deposit paid on all PET plastic drinks bottles, aluminium and steel cans, and glass bottles, with a target of 90% of all material being collected by the third year of the system, compared with existing figures, which for plastic in particular make for dismal reading.

While there is scope for some small retailers to be excluded, the proposals also include plans for £10,000 fines for retailers who fail to comply.

Watered down

On the surface, the proposals appear in stark contrast to the dithering at Defra. In virtually his last major act before moving to a new role as Boris Johnson’s Brexit tsar, environment secretary Michael Gove nailed the government’s colours to the mast in support of an ‘all-in’ DRS system similar to the one planned in Scotland, which would include both plastic and glass, as he apparently rejected the alternative of a watered-down system to target “on-the-go consumption” – which is favoured by many retailers and the likes of the BRC.

But with Gove gone, new environment minister Rebecca Pow, whose predecessor Thérèse Coffey has now also moved on from Defra amid huge ructions in the department, finds herself inheriting an environment brief facing huge questions about timings and commitments to environmental policies laid out under Theresa May’s government.

Defra is still to launch its much-anticipated consultation on a plastic tax, which had been the brainchild of former chancellor Philip Hammond, while a second stage consultation on DRS in England and Wales has been delayed until January/February 2020 at the absolute earliest. Experts believe it will be at least 2023 before a DRS system could be up and running across the whole of the UK.

FDF Scotland CEO David Thomson says the joined-up system deemed so important by the industry is looking “impossible” to achieve. “The timing difference between Scotland, England and Wales will mean that logistics costs will increase for all producers, wholesalers and retailers,” he says “Managing different SKUs means more raw materials, smaller production batch sizes, duplicate storage and increased transport costs.”

Unrealistic timetable

Yet it’s not just Defra facing questions over its DRS plans. In Scotland too, retailers claim the cost and disruption they face to bring the system into place makes Sturgeon’s deadline more pipe dream than reality.

With her government yet to set out its plans for a new arm’s-length body to run the system, huge questions are already being posed about its viability and the price to be paid by industry.

“Pretty much everyone in the industry believes the schedule in Scotland to implement DRS is simply too aggressive,” says one source. “When you add the chaos of Brexit on to this, I believe the timings will change.”

Another retail source agrees: “No one thinks there is any chance of meeting the March 2021 deadline. The current timeframe is not achievable.”

The Scots plan envisages no fewer than 3,000 stores being equipped with reverse vending machines (RVMs).

“In many cases stores will require significant refits, including store extensions, to put machines, warehousing, and logistics into place,” says the source. “Most retailers of scale will need to refit their entire Scottish estate. We think the cost of refitting will be more significant than the cost of reverse vending machines, which the Scottish government estimates at £60m.

“This is an unprecedented project. Refits will vary from six to 18 months depending on the store format, and the complexity of the design, with some small stores needing to be completely redesigned.

“Those refits will require planning, building warrants, and all the other relevant regulatory steps to be taken forwards. It’s also dependent on there being enough RVMs, and indeed enough construction engineers and tradesmen to actually do this work. It’s hard to be certain, but a capital expenditure for building the DRS infrastructure of around £250m for Scotland is not implausible.”

The source estimates it will not be until at least the end of 2022 before the work could be carried out, just in Scotland, with the timescale for a UK-wide process likely to go well beyond 2025.

Glass

With the Scots government insisting it is keen to get on with DRS, it has suggested that retailers could carry out manual handling of cans and glass bottles while the massive refit operation is completed, which the source claims could lead to retailers having to manually handle “thousands of tonnes of glass”.

No wonder the inclusion of glass in DRS has become one of the key battlegrounds.

Earlier this month, trade body British Glass wrote to Scottish environment minister Roseanna Cunningham warning her it would ‘increase the cost and complexity of a DRS system and the risk of the scheme not operating effectively from day one’.

‘Including glass significantly increases the operational cost of the DRS for the scheme administrator due to the material’s low value and greater weight,’ it adds.

‘It will cause significant disruption to glass manufacturers, drinks companies, wholesalers, retailers, importers and the hospitality sector, as well as increasing the cost of drinks in glass bottles.’

With glass recycling already at 67% in Scotland, it urges ministers instead to reform the current producer responsibility model and to increase recycling targets.

Including glass would take the predicted cost of DRS in Scotland from £70m to £120m a year, the BRC claims, and across the UK the bill rises to a thumping £1.4bn (compared with £800m without glass).

Even organisations such as the BSDA, which back an ‘all-in’ system, have argued against the inclusion of glass, as has the FDF, which says it would raise issues concerning safety, hygiene and store disruption.

Meanwhile, Scotland’s decision to include glass, and Gove’s subsequent backing, were branded a “total nightmare” by Iceland boss Walker. Iceland was the first retailer to begin trials of DRS in May last year. It has recycled more than a million plastic bottles since then. But Walker fears the “over-ambitious” Scottish scheme, combined with delays at Defra, will jeopardise the entire project. “Our big message to the Scots is it’s got to be high street-friendly,” he says. “They’re hell-bent on including glass. It would be a total nightmare. The problem is plastic.”

“Our big message to the Scots is it’s got to be high street-friendly. They’re hell-bent on including glass”

However, last month, working with DRS provider Tomra Collection Solutions, Sainsbury’s broke ranks, launching the first trials of DRS to accept glass bottles, PET bottles and cans at its Newbury, Berkshire store.

Tomra, which has RVMs in 60-plus markets, collecting 40 billion used beverage containers each year, and has been involved in Tesco’s DRS trials, claims the inclusion of glass is vital if the Scottish government – and subsequently Defra – are to improve recycling rates.

“For DRS to have the greatest impact on the environment, we believe it should include all three materials – can, PET plastic and glass,” says Truls Haug, the company’s UK & Ireland MD. “Deposit return has the potential to see recycling rates increase to 80% or 90% within 12 to 24 months,” he adds.

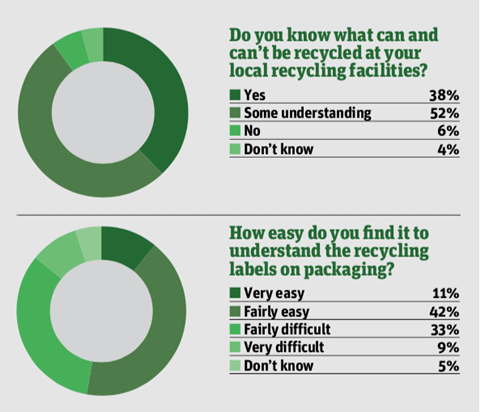

“An all-inclusive scheme reduces consumer confusion about what can and can’t be recycled, ultimately helping to make the scheme more effective.”

Haug claims fears of disruption in stores have been overblown. “We’re operating trials across the UK with retailers of varying sizes, from large supermarkets to smaller convenience stores, and are seeing good uptake from consumers.

“Retailers, and in particular smaller convenience stores, will often cite finding space as a challenge. For that reason Tomra will have a small footprint reverse vending machine ready for the Scottish rollout that can accept PET, cans and glass. This machine will have an even smaller footprint than those being trialled in Scotland today.”

Charging more

The Scottish government’s confirmation that a flat rate of 20p per container, regardless of size, will be applied has also been met with furious resistance from the industry in talks, though ministers appear firmly wedded to the plan. “The industry has major concerns,” says one leading supplier. “The Scottish government seems to be deciding certain aspects of the scheme design such as the level of deposit, thus removing some of the decision levers that are critical to making the scheme work.

“Some manufacturers and retailers are concerned that this will reduce sales of multipacks, for example.”

“This is a major concern – especially for the beverage can industry,” adds another source involved in the DRS rollout. “When DRS was launched in Germany, there was a large movement from can multipacks to large-format PET bottles. Charging a higher deposit on large bottles would reduce this impact and the ability to fine-tune would enable the balance to be adjusted as the DRS settles in.”

Tomra’s Haug, however, argues that a DRS system has to have a sufficient incentive to encourage consumers. “Our experience operating across the globe tells us that the most effective deposit return schemes need to be easy to use, and provide sufficient incentive to achieve high return rates,” he says.

“Our trials have reinforced our belief that it’s important for the deposit value to be high enough to motivate consumers to come back with their containers.

“For that reason we are in favour of a set deposit return rate for all containers, as the consumer will be clear on what they will pay and what they can expect back. We also believe 20p is high enough to incentivise consumers to return their containers rather than simply binning them.

“It is very important to remember this is not a ‘cost increase’ to products – this is a returnable deposit and everyone who recycles through the DRS will get the money back.”

A criminal’s charter?

But will they always? The prospect of a Scottish system coming in potentially several years before it is up and running elsewhere, has heightened fears the industry could targeted by fraudsters on the back of DRS coming in.

One source at a big drinks company tells The Grocer he believes DRS will open the door to “the serious possibility of fraud and corruption at industrial levels”.

“People get confused when they think of DRS and fraud. We’re not talking about a few people getting together and sending a few white vans across the border,” he adds.

“There is a real prospect that criminals will try to sell stock to retailers which has not had a deposit paid on it. This in turn will mean that for consumers the system will not pay out, which risks undermining it completely.”

Another expert source adds: “DRS systems across land borders create real headaches, especially where one of the countries doesn’t yet have a DRS.

“There is a significant risk of fraud that could cost the scheme operator a lot of money. When Germany first went live, lorry loads of bottles were being brought over from Poland and fraudulently used to claim a deposit back. Germany responded by introducing hi-tech labels to limit fraud but it remains an issue.”

And tackling fraud itself is potentially hugely expensive, especially if it results in the need for duplicate SKUs so that all drinks sold in Scotland become Scotland-only SKUs, necessitating the potentially eye-watering cost of duplicate supply chains.

When Defra published the results of its consultation on introducing DRS, in July, it was quick to point to strong backing from more than 200,000 responses to its consultation. It was less vocal about more than 200 of them that pinpointed a raft of ways in which DRS could be used by criminals.

In the document Defra admits manual collection points (of the type now being actively considered in Scotland) were likely to be “more susceptible to fraud than automated RVMs, where the technology can scan containers to confirm their inclusion in the scheme.

‘Respondents were concerned that consumers may try and return out-of-scope containers in a bid to obtain a refund for them,’ says the document. ‘Staff would need to sift returns to confirm the eligibility of the bottles. This behaviour could be countered through barcode scanning, but the volume of returned containers could make this challenging.’

Defra acknowledges there are fears of a raft of different types of fraud, ranging from producers falsifying data over deposits paid, to use of foreign suppliers trying to bypass the system.

Cost concerns

Of course, the more sophisticated the technology used to combat fraud, the more the cost of DRS could rise, at least in the short-term implementation stage.

Some also have grave doubts about claims the system will be ‘cost neutral’. In theory producers will be responsible for the costs of the scheme. Those costs will be offset by the funds created by unredeemed deposits and the sale of the collected materials to recyclers.

Retailers, meanwhile, will have their costs reimbursed through a retail handling fee.

“In theory, producers will pay more, recycling will improve, litter will be reduced and the impact on retailers remains neutral”

“In theory, producers will pay more, recycling will improve, litter will be reduced and the impact on retailers remains neutral,” says one supplier source. “In practice what we fear is a poorly designed scheme could cost the drinks industry tens of millions of pounds each year – including staff time and dealing with bureaucracy related to the scheme. There will also likely be increased warehousing and logistics costs due to ‘Scotland-only SKUs’.”

Such fears are understood to have led to long arguments on the industry implementation group working with the Scottish government, whose next task will be to set up a scheme administrator, likely to be a not-for-profit industry body, to run the DRS system in Scotland. Similar arguments, but on a bigger scale, will face Defra’s Pow, providing she is still in place by then.

Yet both the UK and Scottish governments insist their plans for an all-in DRS can achieve the “step-change” needed to reduce on-the-go littering and boost recycling levels, which sees the UK lagging behind countries such as Croatia, Denmark, Germany and Norway, who all operate forms of DRS.

Defra points out that total return rates of drinks containers in Denmark, Finland, Germany, Norway, the Netherlands and Sweden currently stand at 90%, 92%, 98%, 92% and 85% respectively.

Statistics from charity Recoup show 351,907 tonnes of plastic bottles were collected from UK households in 2017, up 2.5% on the previous 12 months – a record.

But of the 13 billion plastic bottles used each year in the UK, only 7.7 billion (59%) are collected for recycling.

Leap in the dark

Some are sceptical about the impact of DRS and point out that all the various trials held to date have one fundamental flaw – they have been unable to actually test how DRS will work once the 20p fee actually comes into force. It will, in essence, be a leap in the dark.

“DRS hasn’t actually been trialled anywhere in the UK,” admits one expert. “What are called trials are actually just siting an RVM and seeing how that works! All judgements on how a DRS will work here are based on experience in other countries. As out-of-home consumption is much greater in the UK than elsewhere in Europe and our attitudes to the environment are not the same as Scandinavia and Germany, many believe that the UK will not perform as seen in other countries.”

But, a bit like Brexit, others just want the UK government to get on with it. “We were told we had one big opportunity to make a generational change to the environment,” says one supplier source, disgruntled at the slow progress in Westminster on DRS. “We’ve still got that chance. It’s just that we don’t know what generation it will be that makes the change.”

How do Brits take to RVMs?

Iceland was the first multiple to launch a reverse vending machine (RVM) , in May 2018, with the Co-op quickly following suit. Since then, rival multiples Morrisons, Tesco and Sainsbury’s have all developed trials of their own – and three independents in Scotland have also developed trial schemes in conjunction with the Scottish Grocers Federation.

The trials vary enormously in terms of scope, materials collected and deposit paid. For example, while most have only collected plastic bottles, one of Sainsbury’s trial RVMs, which launched in August, accepts glass.

The deposit also varies enormously: Sainsbury’s returns 5p, Tesco and the Co-op 10p, and Iceland 20p – the latter in line with the rate set by the Scottish government in May.

The true impact of RVMs is hard to determine as the final implementation will be a closed loop system. At the same time responses also appear to vary enormously, and some retailers have chosen not to share the results of their trials to date.

As a taster of the likely impact of an RVM, however, Iceland’s year-long trial, involving five Iceland stores has seen more than a million bottles recycled since launch in May 2018.

Interviews with more than 800 customers in June this year showed it was most popular among middle-aged shoppers – those aged 35 to 53 – who made up 53% of users.

Users were more likely to have children at home under 16: 48% for users, 36% non-users, with pester power a key driver.

Forty-eight per cent of people that didn’t use the RVMs said they would be likely to use the scheme in the future once it was explained to them.

Users tend to be more frequent shoppers at Iceland. (Many also claim that the RVM is a key reason for shopping at Iceland.)

Environmental concern was the most important factor driving use (60%), followed by monetary reward (46%).

Could an app negate the need for in-store DRS?

DRS’ first “whole town trial” may eventually lead to reverse vending machines becoming redundant.

Technology is being lined up that may prevent retailers having to spend millions refitting their stores for DRS reverse vending machines.

Startup Cryptocycle is in talks with retailers and suppliers about a system that would provide a unique, one-off code for all bottles and cans, enabling consumers to record on an app when they recycle them.

It claims the scheme will help reduce the possibility of fraud and also has the potential to hugely reduce the cost of DRS by negating the need for in-store recycling facilities.

CEO Duncan Midwood says the company is planning the first “whole-town trial” of its system in early 2020. It will see about 20 recycling facilities placed around a small town, with consumers incentivised to take part in the trial by downloading the app. Consumers would be able to scan a code from the recycle bins on to their phone when they returned products.

“There is a growing industry view that the timing of DRS needs to be delayed to give time to implement a superior DRS design, hopefully ours,” says Midwood. “Time needs to be given to work through all the detailed issues that have not been properly sorted yet.

“Using technology as a solution means DRS may not necessarily mean having to go down to your local Tesco to recycle your products.”

Webinar: Delivering a Deposit Return Scheme

The Grocer is hosting a webinar on Monday 1 October, featuring a panel of experts from across the industry who will answer questions on the much-anticipated launch of a national DRS. The lineup comprises Dr Helene Roberts from Klöckner Pentaplast, the Co-op’s Iain Ferguson, Nick Brown from Coca-Cola European Partners and Simon Stannard at the Wine & Spirit Trade Association.

The webinar will be broadcast at 11am and is free to registered users. Find out more and register now.

No comments yet