As the food and drink industry digests news of the Brexit bombshell there’s a palpable sense of shock, of stunned silence, even panic. But we Brits are a resilient bunch, and it’s clear from the many comments we’ve received that the industry is determined to be positive and to seize the opportunities that present themselves. And not just from lawyers.

There’s even a school of thought that food price inflation will be good news for supermarkets. A note from Bernstein’s Bruno Monteyne suggested Brexit could ease the deflationary pressures eating into supermarket sales and margins. “Every 10% fall in the pound means 3.4% more food inflation. Retailers will be able to pass most of this on to consumers, driving LFL sales, investor sentiment and valuations,” he says.

Bernstein has also found that for every 1% rise in food price inflation, supermarkets achieved a 4-5% increase in their valuation multiples.

So, with the pound falling 10%, how does 3.4% food inflation grab you? Good news?

I don’t think so. Quite apart from the damage to consumer confidence, there’s a price war going. And passing on those prices can come at a cost, as history teaches us.

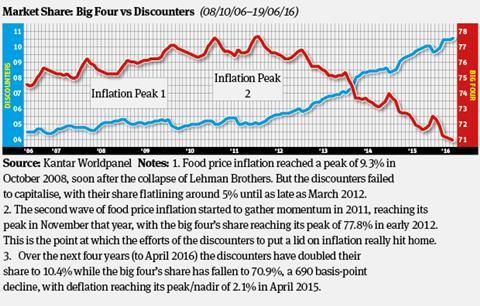

The last time the supermarkets faced into such inflationary headwinds was at the midpoint in the recession (2010-12). It was to prove a watershed moment. The big four passed the price hikes on to consumers. Just as they had done when food price inflation first returned in 2008. In fact they used the inflation to increase profits.

The discounters chose a different path. As well as widening their selection (to reflect modern British trends) and improving quality, they locked prices down and kept them locked (while the supermarkets created a blizzard of promotions to distract the consumer from their intent).

And the rest is history. This was the point at which the discounters not only diverged from the big four on price. It’s when their market shares started to converge.

We are at a similar inflexion point today.

No-one knows when food price inflation will start to kick in in earnest. It depends on the source, on the cost of goods relative to the selling price, it depends on whether you’ve hedged, on the shelf life, as well as the particular currency in which those goods or ingredients are traded. But the day after the result, Ministry of Cake, a cake and dessert manufacturer, was reporting a 33% increase in the cost of some ingredients. Overnight.

But it also depends on the supermarkets themselves. Whether they choose to pass the price hikes on. Supermarket leaders always love to claim their actions are governed by what consumers are telling them. This is complete bunkum, of course, or at least it has been for the big four in recent years, as they have learned to their cost.

The question is: will they make the same mistake twice? Or take the hit, or some of it, on the chin?

Aldi and Lidl aren’t immune from the impact of weak sterling, of course. They both source around two-thirds of their selection from UK suppliers. But if they choose to absorb food price inflation while the big four pass it on, valuations will, like their sales, surely slump still further.

What the supermarkets desperately needed was population growth. That was a strong possibility in the event of Britain remaining in the EU. What the supermarkets must face up to instead is goods inflation and the prospect - whatever your views on the result - of an economic downturn. It is not a good mix.

No comments yet