Shoppers have been facing shortages of key fruit and veg items across major supermarkets since the end of last week, leading to buying restrictions, increasingly panicked newspaper headlines, social media outrage and wall-to-wall media coverage.

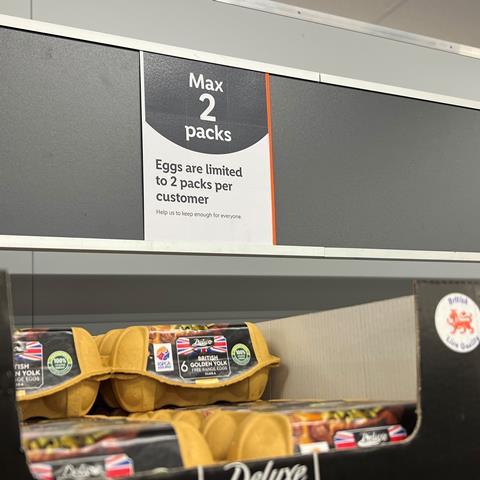

Those shortages have led several supermarkets to impose buying restrictions on certain items.

The British Retail Consortium cited “difficult weather conditions in the south of Europe and northern Africa”, which had disrupted harvests for products such as tomatoes and peppers. But critics have pointed to plentiful produce elsewhere in Europe.

🥒Shortages of fruit and veg?🍅

— The British Retail Consortium (@the_brc) February 21, 2023

At the moment poor weather conditions in Spain and Morocco have disrupted harvest for some fruit and vegetables including tomatoes and peppers, but rest assured retailers are doing all they can to sort it!

Industry insiders point out the shortages – of which growers have been warning about for many months – are also driven by chronic low returns and soaring costs, which have been exacerbated by ongoing issues around Brexit. Unless things change fast, they warn these shortages could become a consistent theme for the foreseeable future.

So just what is the truth? How bad could the shortages get, and just how connected to Brexit is this crisis?

Who’s rationing what? And why?

We may not be at the levels of panic-buying seen during the pandemic just yet, but the shortages have already prompted some extreme behaviour from shoppers.

The Metro newspaper reported on Thursday one shopper had been turned away after trying to buy 100 cucumbers at a Lidl store in Merseyside this week. And in the face of growing shopper unrest, particularly on social media, some retailers have chosen to act now by limiting the amount of produce that can be bought.

At the time of writing, rationing was in place at Aldi, Asda, Morrisons and Tesco.

Aldi is rationing the sale of peppers, cucumbers, and tomatoes to three units per person “to ensure as many customers as possible can buy what they need”.

Tesco is also limiting the same lines, to three items per customer as a “precautionary measure” to maintain stocks. This is “in light of temporary supply challenges on some lines”, the retailer says.

— Tesco (@Tesco) February 23, 2023

Meanwhile, Morrisons is capping two items per customer across tomatoes, cucumbers, lettuce and peppers.

And Asda is limiting the purchase of eight fresh produce lines – comprising tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, lettuce, salad bags, broccoli, cauliflower and raspberries – to three of each per customer.

M&S also tells The Grocer it is looking at “alternative supply routes” to mitigate challenges.

Other retailers are still playing down issues with supply. The remainder of the supermarkets contacted by The Grocer this week stated they had no plans to introduce rationing – and claimed availability in specific stores or online was not representative of overall availability.

What is this doing to prices?

There is so far little evidence that tight supply is leading to further inflationary price moves in retail. But it is already feeding into huge wholesale price hikes. Tim O’Malley, group MD of Nationwide Produce, points to its data, which shows the spot price for boxes of some vegetables are up two or three times as much as they would be at this time of year.

Cherry tomatoes have increased from an average of £5 to £6 per box to £17 per box, while yellow peppers are up from £8 to £9 to £22 per box.

“I can honestly say that in the 40 years I’ve been in this trade, I’ve never seen such high prices across such a broad range of products for such a prolonged period of time,” says O’Malley.

Credit to Liz Truss: when she ran the country, there were at least fresh vegetables available to measure her time in office.

— Henry Mance (@henrymance) February 22, 2023

What part has the weather played?

In a scenario reminiscent of 2017’s salad crisis, bad weather has been touted as the main driver of this winter’s shortages.

This time of year is when the UK depends the most on imported fresh produce, making the UK particularly vulnerable to supply chain volatility and weather disruption. Indeed, the BRC says the UK sources as much as 85% of its tomatoes from the EU in March and 90% of its lettuces. UK supply accounts for just 5% and 10% respectively.

Environment secretary Thérèse Coffey this week told MPs the UK imported a total of £1.5bn worth of fresh produce from Spain, and £340m from Morocco in 2021 – which clearly adds up to a significant proportion of the UK’s total requirements. Data from The Grocer’s 2022 Top Products survey puts total fresh produce sales in retail channels at more than £10.5 billion last year.

So, when the weather is bad in key growing regions such as Spain and Morocco – which is increasingly seen as a valuable alternative supply source – the impact can be quickly felt on UK supermarket shelves.

“Weather conditions in Spain and Morocco had been abnormal last year, beginning with a drought and high temperatures in the summer before a mild autumn and a severe frost over winter,” says O’Malley.

Bad weather in Britain has also impacted products for which the UK can typically supply itself year-round too, including carrots, cabbage and cauliflower, he points out. “There is no way” UK supply will be sufficient to fill any gaps this year, he warns.

And the current supply situation is likely to lead to a “big import window, and import equals expensive” O’Malley adds, as retailers scramble to source produce from other parts of the world – inevitability at premium prices.

As a result, he predicts the total amount of produce the nation imports year-round is likely to rise from 67% on average to 75% this year.

Not a single tomato to be had in Cardiff(Sainsbury’s, Lidl, Morrisons)#EmptyShelves

— Jonny Fawr 🏴 (@JonnyFawr) February 17, 2023

Apparently “supply issues”#BrexitBritain

Also British greenhouses cannot afford to put on the heating#ToryCostOfLivingCrisis pic.twitter.com/dkHGX7MF9w

For example, the UK-grown yield of onions – of which the UK typically grows 450,000 tonnes annually – is down to 350,000, meaning an extra 100,000 tonnes will have to be imported to meet UK consumer demand. As a result, O’Malley predicts far greater than normal volumes will have to come from Egypt, Chile, South Africa, New Zealand and Tasmania. “Not great for climate change, is it?” he says.

British leek farmers also warned of short supplies this week due to adverse weather conditions. Tim Casey, chairman of the Leek Growers Association, says yields are down between 15% and 30% and he is “predicting the supply of home-grown leeks will be exhausted by April, with no British leeks available in the shops during May and June, and consumers having to rely on imported crops”.

But what about the ongoing problems with UK production?

Unpredictable weather is by no means the only issue facing UK growers. UK production is contracting due to soaring input costs and dwindling returns. Many glasshouse growers are not stocking some or all of their facilities in order to save money on heating, following eye-watering energy price hikes.

According to the NFU, this means salad production yields are expected to drop to their lowest levels since records began in 1985. Both energy and soaring input costs such as fertiliser have been the key drivers of the decline, while the spectre of labour shortages also continues to plague the sector.

The cost of production has risen by up to 50% since 2019, but the prices paid by retailers and food manufacturers haven’t kept the same pace, NFU president Minette Batters explained at the NFU Conference earlier this week.

“Farmers and growers must get the fair return their hard work justifies,” she urged. “Volatility, uncertainty and instability are the greatest risks to farm businesses” with “consequences being felt far beyond farming”, Batters added.

Unless that changes, it looks like production will continue to fall. The NFU says 56% of growers surveyed in a recent poll had seen an average fall of 19% in 2022 production, and expect of a further fall in production of 4.4% in 2023.

This comes on top of the union’s Promar report, published late last year, which estimates businesses could be cutting back on planting by up to 20%.

Isn’t it really about Brexit?

A variety of hashtags such as #BrexitHasFailed and #BrexitFoodRationing have been trending on social media this week, accompanied by claims of plentiful supply in other European countries.

While Brexit is not the leading factor causing these supply issues, it is not completely without blame, industry experts say.

One senior food industry insider says Brexit made the situation worse. “Where there’s a reduction in supply due to weather, it’s a lot easier to supply those in the single market” due to the lower cost and reduced bureaucracy involved, they point out.

Indeed, on social media, many have pointed to fully-stocked shelves on the Continent. One Eurostar employee called Paris “tomatoland”, pointing out it’s only “two hours away from London”. Others have even posted photos of supermarkets in war-hit Ukraine showing shelves full of fresh produce.

Good afternoon from Tomatoland! Just over 2 hours by train from London. Need to stock up? Jump on a eurostar... pic.twitter.com/gVu9XLCCSp

— Justin on eurostar (@EurostarJustinp) February 22, 2023

If you want to find endless fresh food with multiple choices of each product I highly recommend a trip to … the European mainland . There’s no shortages there . U.K. is slim pickings now with the same tedious offerings every week #brexit pic.twitter.com/wiT7h0Ti7H

— ciaran the euro courier 🇪🇺🇮🇪 (@vanmaneuro) February 19, 2023

“It’s absolutely true that in a tightened supply situation, Brexit is causing supply shortages in the UK. It may be indirect, with market traders clearing shelves and causing issues, and they’re rationing so real customers can get them,” explains the industry source.

“Sometimes it’s a displacement effect. But when supply is short from the Continent it highlights further the reduction in supply over here.”

Mike Parr, MD of logistics provider PML, backs up that point. He is “repeatedly hearing on the ground that producers are simply not interested in shipping fresh produce to the UK because of the unacceptable cost of transportation, coupled with the unprecedented level of paperwork and well-documented extensive delays associated with imported goods”.

What is the government doing about this?

So far, it seems to be firmly in denial. Thérèse Coffey stressed in parliament this week the UK has a “highly resilient food supply chain and is well equipped to deal with situations that have the potential to cause disruption”. She added: “We continue to expect the food industry to mitigate the supply problems through alternative sourcing options.”

Coffey went on to face stiff criticism from delegates at the NFU Conference this week by playing down the impact of the crisis and stating “we can’t control the weather in Spain”. Her denial that the wider egg and pig sector were also in crisis faced further barbs from angry farmers.

One senior food sector source says the government has “got itself into a pickle with their focus on water quality, air quality and biodiversity – food is very much on the back seat”, in echoes of the criticism levelled at Defra secretaries from Truss and Gove to Leadsom and Eustice.

What’s going to happen next?

Don’t be surprised to see more retailers imposing purchasing restrictions. This crisis is due to continue well into the UK season from the spring onwards, suggest multiple sources. And by then, the true scale of the decline of UK production should also become apparent.

“Britain is going to stop producing so we’re going to see more food inflation coming through,” suggests one senior retailer source.

Due to the issues around profitability in UK growing, “we’re not going to have many tomatoes grown in Britain. We’re not going to have many cucumbers. So that imported food inflation will continue above 3%. We’re highly dependent on Spain and it’s failed. Morocco is the back-up and it’s failed. The Dutch are selling into Europe. And the British growers have all packed up.”

It might be time to start looking at an allotment.

No comments yet