Food is at an ever growing risk of theft, as criminals seek ‘low risk, high reward’ targets. And retailers and manufacturers are playing into their hands

In the early hours of a cold November morning, as a lorry driver slept in a layby half a mile from Doncaster, a sudden noise awoke him from the back of his truck. He leapt from his bunk, started the engine and drove away without looking back. Within minutes, he reached his delivery point at a nearby Asda, begging for someone to let him in.

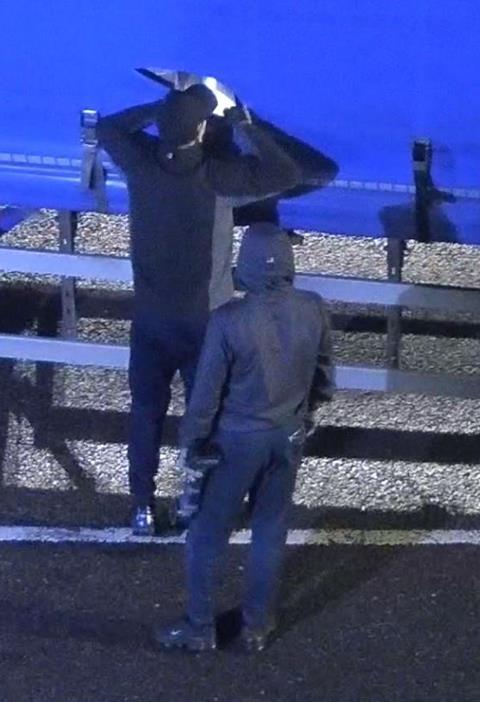

Once safely inside, the source of the noise quickly became clear. The truck’s side curtains were slashed, with two pallets of products, including £5,000 worth of Filippo Berio olive oil, now missing.

It’s a frightening tale, yet one many HGV drivers across the country know all too well. Travel along the M1 these days and you’ll often see parked lorries with their doors open simply to show there is nothing inside worth stealing. “It’s a sign of the times,” said Walter Zanre, Filippo Berio’s UK MD soon after their robbery.

The olive oil producer is just one of several high-profile food robberies recently. Last month, 200,000 Cadbury Creme Eggs were stolen from an industrial estate in Telford. While the police’s announcement that it had caught the individual “presumably purporting to be the Easter bunny,” opened the floodgates for jokes on social media, the real story is less funny for those involved. The suspect, 32-year-old Joby Pool, allegedly used a power tool and tractor unit to break into an industrial unit owned by SE Logistics at Stafford Park, before stealing confectionery worth nearly £40,000. He was later found by local police some 45 miles away.

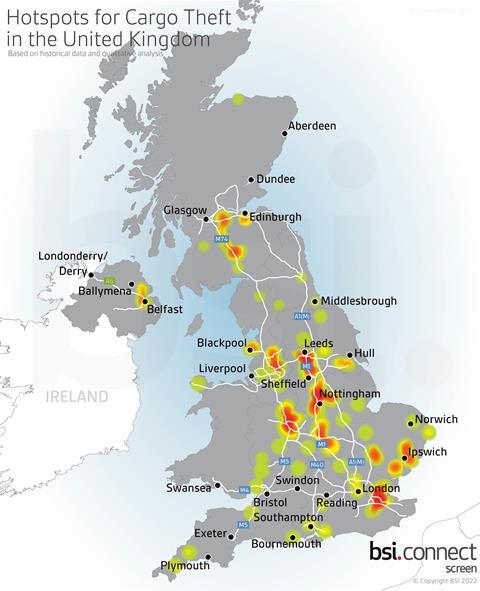

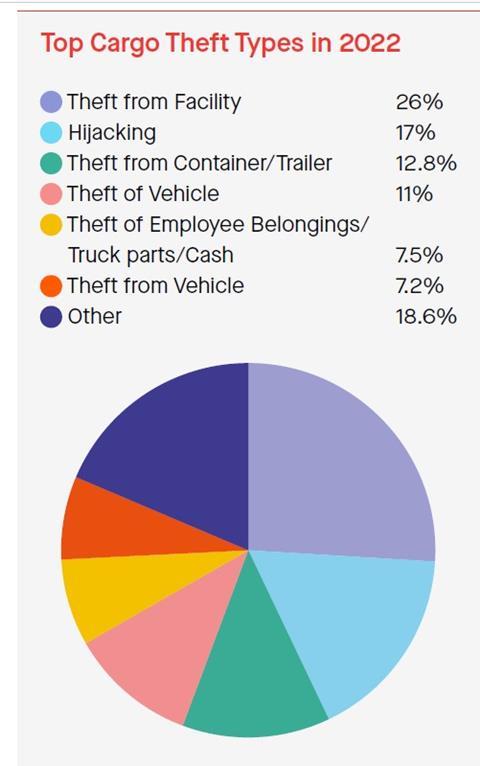

Both robberies are examples of a much larger issue taking place across food supply chains, with food and drink now making up 17% of cargo thefts in 2022, a rise of 3ppts on the year before, according to the British Standards Institution’s (BSI) – greater than any other sector.

In the UK alone, there were over 5,000 reports of freight crime in the country last year, with a total value around £66m, data from National Vehicle Crime Intelligence Service (NaVCIS) shows.

The true costs, however, could be up to 10-times higher, says NaVCIS Freight Desk field intelligence officer Mike Dawber.

“There are hidden costs that you don’t necessarily see, such as insurance company costs, policing and criminal justice, retail values which can be anywhere between four and nine times the loss value, brand and reputational damage, damage to trucks and trailers and associated costs to haulage companies… we’re looking at about £700m per year just from cargo crime,” he explains. This is a hefty increase from just over 10 years ago, when a 2011 government lorry crime prevention study found freight crime cost the UK economy about £250m a year.

When Mike Dawber joined the police 20 years ago, criminals were “holding banks and post offices up with firearms to steal money.” Now though, working as a field intelligence officer in the vehicle crime unit, he’s found “that’s considered too high risk.”

Food and drink cargo theft, on the other hand, is what black market insiders call “low risk, high reward”, says Dawber. Criminals can sell goods at bigger margins in the alternative market – up to 90% – and goods are hard to trace because they are consumed quickly.

High-value goods like alcohol are a criminal’s favourite. James Brook, a cargo & freight senior specialist at the British Association of Cargo Surveyors (BACS), recalls a recent incident where two trailers loaded with alcohol worth £330,000 for a major supermarket were stolen from a haulage yard during the night. Insurance estimates revealed those figures could rise to nearly £1m when considering alcohol duty and excise.

“In times of economic strain, the most valuable commodities will always get targeted,” says Jim Yarbrough, a global intelligence program manager at BSI, pointing to rampant egg theft across Europe when shortages hit last year. Similarly, wheat loads were targeted by criminals after the cereal shot up in price when the conflict in Ukraine halted supply.

It’s not just that crime has become more profitable. It’s also become easier due to supply chains growing more vulnerable since the start of the pandemic. “The pandemic and subsequent supply chain crisis meant freight was constantly off schedule and in the wrong place,” Yarbrough explains.

He adds: “When ports are congested, goods can be left to pile up in unsecured locations at high levels of over-inventory. A theft from a warehouse or a port that is experiencing a high level of overflow is much easier to pull off than, say, a hijacking.”

But it’s when freight is in transit that it becomes a perfect target, especially when moving through quiet, open areas with easy access and minimal security facilities like laybys, truck stops and industrial estates.

“A warehouse or port experiencing a high level of overflow is much easier to pull off than, say, a hijacking”

The most common modus operandi for thieves include slashing side curtains, cutting holes into trailer roofs, and tampering with seals. Some bolder thieves will even break into hauliers’ yards, hook up a pre-loaded trailer to their own trucks, and drive away.

When these tactics don’t work, some resort to impersonating supermarket buyers or stealing drivers’ identities to divert larger trailers of goods. Food traffickers “are very entrepreneurial”, says Louise Manning, professor of sustainable agri-foods systems at the University of Lincoln. “The minute there is a higher deterrence in one activity, they’ll switch to another.”

Dawber says criminals are willing to travel far and wide to do these jobs because the legal penalties are simply too weak and the rewards too tempting. Take Creme Eggs robber Joby Pools, who was previously convicted for a similar stolen goods offence in 2019. He’s been sentenced to jail for only two years for the Cadbury heist. “That guy was from Leeds and he was caught down in Telford,” Dawber says. “Some of these guys are travelling 150 to 200 miles just to commit these types of offences because it pays off.”

During the trial, the prosecutor told the court this was “clearly an organised criminal matter” as “you don’t just happen to learn about a trailer with that kind of value being available”.

A crucial piece of the puzzle is that the criminals themselves know what they’re doing. “They understand supply chains,” says Dawber. “They know which haulage companies have which contracts, and they know which routes they take and where their schedules will force them to take rest breaks.”

This inside knowledge is why stolen goods often reappear in legitimate supply chains – including convenience shops, market trader stalls, and platforms like Facebook Marketplace, Gumtree and eBay.

Every once in a while, goods will even permeate back to big supermarket shelves: “We had a lorry load of canned tuna worth about £200,000 that was stolen in May last year. That tuna reappeared before Christmas on supermarket shelves for sale,” Dawber recalls, though he won’t name the retailer.

The reason many individuals are reluctant to name names is the effects on businesses can often be reputational as much as financial. “Companies don’t want to be deemed as not having a grip on their supply chains,” says cargo specialist James Brook.

But the impacts of cargo crime can be personal too, with the HGV drivers on the frontline often suffering the deepest cuts. Two thirds of cargo crime victims say it is a trauma that has affected their mental health, according to a survey by haulage smart-payment specialists SNAP.

“Imagine waking up in your truck and suddenly you realise your curtains are all slashed and your load’s gone,” Dawber says. “Now you’ve got to explain to your boss what happened and you find yourself in the midst of an investigation. Of course it’s going to be traumatic and upsetting for the driver.”

Extremely violent encounters are uncommon as thieves prefer a non-confrontational approach, says Brook, although he has heard of several close run-ins. There is also evidence that 5% of cargo theft victims have suffered assaults with sleeping gas, according to SNAP’s survey.

Trade bodies and unions like the Road Haulage Association (RHA) often publicise the mental health resources they have in place so members are aware they can reach out for help if they ever find themselves involved in a theft incident.

Safe vs secure

The perceived risk is now so pervasive, it’s even starting to hurt recruitment. “It doesn’t make the industry a very attractive proposition if criminal activity is rife,” says Tom Cornwell, policy lead at the RHA.

That is exactly why trade unions and law enforcement have been calling for safer parking areas for years. The RHA has repeatedly said there aren’t enough provisions for lorries to park in the UK, with a recent survey showing lorry parking capacity in the UK was at “critical level”. This is forcing truckers to park in unsafe locations like laybys. Other times it’s retailers and brands’ margin-squeezing tactics that are causing hauliers to risk their own safety, adds Dawber.

“The food industry are almost their own worst enemies because they’re constantly trying to drive down delivery prices so they put the squeeze on the haulage companies to continually drive down the costs.

“Some hauliers running on very small tight margins have no choice but to waive the £60 overnight parking fee and just take the risk.”

When drivers do opt for roadside parking areas, there is also the issue of safe versus secure accreditation. The former offers basic conditions like adequate lighting and CCTV presence, while the latter means security is much tighter. However, only two truck parking facilities in the whole of the UK have that stamp.

Things seem to be improving, though. The British Parking Association has just devised a new secure parking accreditation for truck parks and motorway service stations, which will be rolled out across the country in coming months.

And many food and logistics companies, like Pladis and Goldstar Transport, are actively working in partnership with groups like NaVCIS and TAPA to strengthen their operational security. Logistics giant Wincanton tells its drivers to never engage with the criminals and often shares intel from its policing partners to improve situational awareness so that colleagues are able to identify a theft attempt more easily and report it to police.

Plus the Department for Transport & National Highways recently launched a £100m matched-funding scheme for businesses looking to improve the security of their locations and create a safer environment for drivers. It’s a long-term investment that will pay off, Snap MD Mark Garner argues. “By offering a location with higher security, site managers can reduce insurance costs and attract customers willing to pay a little extra for security and peace of mind.”

Beyond increased security, Manning says risk assessment needs to happen across the entire supply chain. A holistic view of what it means to have robust chains includes working with suppliers to map out risk-prone areas and implementing a cargo theft risk register, as well as a buddy system so drivers always have someone on call.

“It comes down to a duty of care, recognising that supply chains are vulnerable to this – especially right now – and then looking at what mitigation strategies you can put in place.”

The issue at the heart of all this is perhaps that cargo theft remains an unreported issue. But raising awareness so that everyone, from producers to haulage companies and warehouse operators, could be key to tackling the problem.

“We need the industry, the general public, the government, and police forces to recognise the seriousness of the nature of some of these crimes,” says the RHA’s Cornwell.

After all, the dangers of cargo theft are not something anyone wants to learn the hard way.

No comments yet