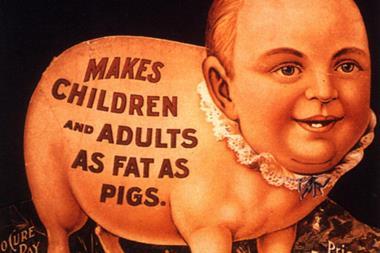

Supermarket prices may have risen well above Mervyn King’s inflation-based target in the past year or two, but we’re still spending far less on food than 150 years ago.

To celebrate the 150th anniversary of The Grocer, we compared this week’s Grocer 33 mystery shopping basket (cost £93.95), with an equivalent ‘basket’ from 1862. The basket would have set a customer back an eye-watering £1,254 - 13 times the amount paid today, based on an average earnings measure of inflation.

Although wages have increased substantially over the past 150 years, the decrease also reflects big supply chain advances.

Once-exotic items have, unsurprisingly, come down in price the most. In 1862, pineapples were rarely traded, but when they were, sold for 5s. That’s £149 in today’s money, or nearly two days’ pay for a builder working in 1862, who earned 2s 10d for a day’s labour.

Everyday essentials have also become dramatically more affordable - leaving shoppers more money for holidays, clothes, games and iPhones. In 1862, with 250g of tea sold for the equivalent of £49.17, 500g of sugar for £16.41, and four pints of milk for £4.96, a builder’s brew was still a treat for most.

According to Asda’s Income Tracker, the average UK family spent £58.42, or 7.7% of their income, on food each week in October 2011. The percentage has risen since the tracker’s inception in January 2007, when families spent 6.8% of their gross income on food.

However, if a labourer in 1862 spent this proportion of their income on food, they could only have afforded a single ham sandwich - comprising two slices of bread, 100g of ham a fifth of a lettuce and 10g of butter - per day.

A dozen eggs also now costs 768% less than 150 years ago, when at 9d they were the real-term equivalent of £22.30.

England’s chickens failed to lay enough eggs to satisfy the English appetite for bacon and eggs for breakfast, and boiled or poached eggs for tea, as the population tipped towards an urban majority, according to the Provision Trade Federation.

In contrast, in 2010, the British Egg Information Service estimated 80% of the 11.27 billion eggs consumed in the UK were produced here.

However, Martin Caraher, professor of food and health policy at City University, said prices were unlikely to fall any time soon oil prices continued to rise. “We depend on oil,” he said. “We use it in fertilisers, to run tractors, to bring it to the factory, process and distribute it and go to the shops to buy it.”

Source

Elinor Zuke

No comments yet