It’s been a bloody battlefield for the wholesale sector in the pandemic. What’s happened and what’s the outlook?

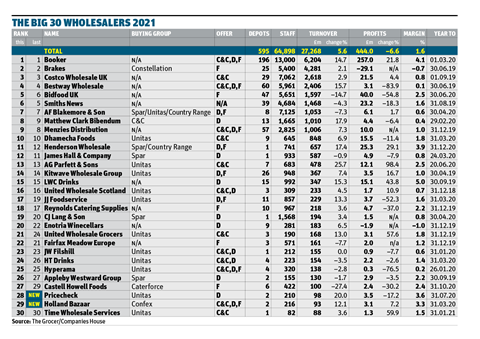

The Big 30

It’s been a year like no other. And let’s hope, as the nation tentatively starts to move out of the nightmare that has been the Covid-19 pandemic, there will be no more years like it to come.

Just 12 months ago, the biggest issue dominating the wholesale sector was whether businesses should move to a delivered or cash & carry model. That was before it become clear how big an impact this new virus would have on the sector, and life in general.

For wholesale, it has been a tale of the good, the bad and the ugly. On the good side, there have been huge sales increases in grocery. On the bad, a breakdown in communications with suppliers, leading to major availability issues. Then there’s the downright ugly impact of the hospitality shutdown on foodservice specialists – a situation that has only been made worse by a lack of sector-specific support from government. And that has turned upside down the fortunes of wholesalers.

For a long time, the considered wisdom was that grocery wholesalers should increase their presence in foodservice. That made sense as the lines between food to go and takeaway blurred, and more and more food was consumed away from home.

But ironically, the operators that resisted that move have fared best in this new climate. Wholesalers such as Parfetts, Bestway, JW Filshill and Dhamecha saw a sharp spike in sales last March as shoppers flocked to convenience stores in the initial throes of lockdown. They have been able to maintain higher-than-normal revenues ever since.

“Since the start of the pandemic more of our retail customers shopping through C&C,” notes Bestway Wholesale MD Dawood Pervez, “as delivery slots have been limited, and customers wanted to make sure of availability of supply to meet their growing demand.

“Grocery, fresh, frozen and alcohol sales have been the key beneficiaries in terms of upsell during this period,” he adds.

JW Filshill chief sales and marketing director Craig Brown says sales have increased 25% during the pandemic. “We have had a year of unprecedented growth. Our convenience partners have averaged almost 20% growth in their retail sales for the full year,” he says. “Our ability to cope and deliver exceptional service during times of peak trading has exceeded existing customers’ expectations and delivered a greater number of enquiries to join our symbol group than ever before,” he adds.

For many wholesalers, that ability to adapt to such a tough period and high level of demand is a source of pride. “Seeing our staff handle the intense and dangerous period of the first lockdown was the highlight of the year,” says Time Wholesale Services MD Sony Bihal. “Our staff pulled together, planned and served. I am very proud of our team.”

But this extra work hasn’t necessarily led to increased profits. Parfetts joint-MD Greg Suszczenia can testify to that. “We had some dark days very early on. The business has done well, but it’s not been easy in any way, shape or form. We haven’t massively improved our margins,” he explains.

Extra financial costs for wholesalers came in terms of hiring more staff and buying in PPE. This had an impact for cash & carry operators, of course – but for those wholesalers with company-owned stores, it was accentuated still further.

“The business has done well, but it’s not been easy in any way, shape or form”

Like AF Blakemore, which incurred costs of over £1m implementing Covid-19 measures, spending £250,000 on installing in-store screens across its managed estate. As a wholesaler that deals in both sectors, Blakemore was also one of those whose improvements in grocery sales were either mitigated or cancelled out by foodservice declines.

There was a similar story at the UK’s biggest wholesaler, Booker. “Caterers have been restricted due to lockdowns. Retailers have seen increased demand,” says Booker CEO Charles Wilson, who stepped down after 16 years at the helm last month.

The net effect, alongside the strains of the pandemic, has been a negative impact on the bottom line. “Profits are depressed by the decline in catering sales and the increased costs of Covid,” he reports.

But he’s keen to emphasise the positives. Premier, Londis and Budgens have had record years, for one. “Overall Booker is in good shape,” says Wilson. “Customer satisfaction has been good. Colleagues and customers have done a brilliant job at keeping the nation fed during extraordinary times.”

It’s a strong legacy to build on, adds Wilson’s replacement Andrew Yaxley: “What a privilege it is to continue the Booker journey and take over the reins from Charles. Booker is a great business: from our people, to the simplicity of its operation, along with the focus and passion for customers.”

Another operator experiencing mixed fortunes – albeit on a much smaller scale – was north London wholesaler Holland Bazaar. Half the wholesaler’s business is cash & carry, 10% delivered wholesale and 40% foodservice. Although the foodservice side did take a hit, director Mert Ucar explains the business has still managed strong single-figure sales growth.

“The closure of restaurants and hospitality outlets had an impact in a negative way, but we have a multichannel customer base (restaurants, coffee shops, takeaways, convenience stores, secondary wholesalers and even households), which is one of the key reasons for our 8% growth during the Covid-19 crisis,” he says. “Although one side of our customer base was hit, sales on the other side went up significantly.”

Supermarkets cashing in on wholesaler territory

The big four are moving ever further into wholesale retail territory. This week, Morrisons extended its wholesale supply agreement with McColl’s by a further three years (to 2027) and 230 stores (ie the full estate).

Meanwhile, Sainsbury’s trial with SimplyFresh is scaling up, and speculation is increasing over whether the Issa brothers will begin using Asda to supply their EG forecourt estate, which could see Spar sidelined after 17 years.

“We haven’t seen the full impact of this changing landscape yet,” says FWD CEO James Bielby. “But it’s fair to assume it will lead to consolidation in the indie retail sector as supermarkets erode wholesale share.”

But the pandemic also appears to have emboldened supermarkets to target foodservice business too, including schools, nurseries, care homes and more.

In October, Morrisons launched a wholesale food box service aimed at not-for-profit and public sector organisations such as food banks, local councils, universities and schools which needed hygiene products and food in bulk for the vulnerable: a service that was also being fulfilled by foodservice wholesalers.

In January, Asda also launched its ‘Priority Pass’ scheme for nurseries, customers who have traditionally favoured shopping at cash & carry locations. It offered 5,000 childcare providers first-in-line recurring delivery slots.

Wholesalers are also reeling from the government’s u-turn in reintroducing £15 free school meal vouchers following the Chartwells fiasco.

This is the most acute example of supermarkets taking revenue directly from wholesalers – but to be fair it was facilitated by government not the mults. Nonetheless there’s a feeling, as Bielby put it in January, that with “supermarkets long [having] had their eye on expanding into out-of-home food, government policy is aiding that ambition.

“It is incredibly damaging to food supply, to vital services and to the diversity of food provision in the UK,” warned Bielby.

With Amazon an additional threat, foodservice operators hope their customer service will endure after lockdown. But new habits have formed and digital investment in the foodservice sector has inevitably been cut.

Demand challenge

Sales went up so significantly, in fact, that getting enough products to meet that demand was the tricky part. Early on in the crisis last spring, grocery wholesalers were struggling to source their fair share of products from many suppliers.

Bestway was one of those affected. “Getting supplies of certain in-demand products was challenging during the start of lockdown,” says Pervez. “This was partly due to demand from large supermarkets.”

So he decided to take action through the Federation of Wholesale Distributors (FWD). Pervez was initially reticent about raising the issue, he told The Grocer last year, mainly out of fear of offending peers on the foodservice side. He was uncomfortable about seemingly complaining that his business and other grocery wholesalers were unable to keep up with demand when many foodservice operators had lost most of their sales overnight due to the hospitality shutdown.

However, the FWD recognised the severity of the issue, seeking to understand the cause and resolve it. The cause was understandable but misunderstood. To meet soaring demand, suppliers focused on a stripped-down range of bestselling lines to keep the food and drink supply chain moving and feed the nation. Many traditional convenience pack sizes and products with price-marked packs were cut at this time, leaving wholesalers and convenience operators vying for the same packs as the supermarkets.

Suppliers were then basing where to allocate product on algorithms created by previous purchasing history – which wholesalers didn’t have, meaning they missed out. The frustration spilled over particularly when suppliers such as Heinz launched a direct-to-consumer operation, despite struggling to meet wholesale orders.

“The wholesale community came together immediately”

In April the FWD, along with the Association of Convenience Stores, working with Defra, persuaded the Food & Drink Federation to write to all supplier members calling on them to ensure fair allocations to the wholesale and convenience channels. A move that saw the situation begin to resolve almost immediately.

“Overall, we have found supply and service has since improved as both parties try to work together and manage forecasting on a day-to-day basis,” says Pervez.

That’s a crucial point here. Because one defining feature of the crisis has been the newfound solidarity between previously fiercely competitive rivals across different sectors, led by the FWD, as well as other key industry figures.

“The wholesale community came together immediately,” says Country Range Group CEO and FWD chairman Coral Rose. “A WhatsApp group was set up by FWD and a year later it is still being used for immediate communications. It has brought the FWD much closer to its members and given them a greater understanding of what the trade association can do.”

That solidarity has been a crucial tool in highlighting the biggest issue in the industry: the plight of specialist foodservice wholesalers. The sustained periods of hospitality shutdowns, on-off reopenings, tier restrictions and school closures have devastated businesses of all sizes, from the foodservice giants like Brakes and Bidfood to smaller specialist and regional operators.

Despite being chosen to lead the government’s shielding box delivery programme to feed the most vulnerable, Brakes and Bidfood have both confirmed major structural reorganisations, each affecting more than 1,000 jobs.

“The Covid-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the foodservice industry, with the closure of most hospitality customers, some of whom have since announced administrations or permanent site closures,” says Brakes communications director Matt Stewart. “We are expecting a lengthy recovery period, and the industry is likely to be materially smaller as a result of the pandemic.

“In order that we can continue to succeed in the future and service new and different customer needs, we have reviewed our entire business, resulting in a number of changes, which have included the closure of some smaller depots and overall reduction of colleague numbers,” Stewart adds.

Bidfood CEO Andrew Selley tells a similar tale. “Covid-19 has had a devastating effect on the hospitality industry and the foodservice distributors that supply it,” he says

“During this time, we have been able to pivot our business model and offset some of the impact by offering home delivery and click & collect services to consumers, and by delivering government care packs to the vulnerable. However, the extended restrictions on many of our customers, and the uncertain market conditions we continue to face, mean that it is highly unlikely that our business will return to the trading levels we saw prior to Covid-19 for some time.”

FWD CEO James Bielby on the year in wholesale

As we come to the end of the first year of Covid-19’s pernicious influence, the sheer resilience and resourcefulness of the brilliant wholesale sector is clearer than ever.

Throughout the year, wholesalers resolutely decided that whatever the virus threw at them, they wouldn’t let their customers down.

Wholesalers went out every day to fulfil and distribute orders, even when the dangers weren’t fully known.

Within days of the first lockdown, foodservice wholesalers flipped their business models to provide delivery services to members of the public struggling to get supermarket slots – using entrepreneurial spirit to help supply the public and offload some excess stock, too.

Throughout the year wholesalers stayed open to ensure schools, hospitals and care homes got vital supplies, trading at a loss to do so. Then cash reserves were exhausted further to stock up so hospitality customers could trade from the first day they were allowed to.

Grocery wholesalers also came out swinging to fight for fair allocation for the channel when sales boomed but supplies didn’t keep pace. That’s without mentioning the acceleration in the collection, analysis and sharing of data.

So there’s plenty to be proud of. For FWD, we can point to the fact that the squeezed middle of the food supply chain has never had a higher profile with ministers, MPs, officials, national media or the public in general – and we couldn’t have done that without members who have shouted about problems they have faced.

Thanks to these efforts, wholesale now has a dedicated team in Defra.

We have always said wholesale is innovative, adaptive and resilient, but the past 12 months have proved that beyond doubt. Perhaps a little more understanding of how food gets to the shelf or menu has percolated into the nation’s consciousness as a result.

James Bielby

Direct to consumer

As Selley suggests, pivoting towards more direct-to-consumer trade has been one source of respite for these beleaguered businesses. One foodservice specialist to have used the model to successfully buck the prevailing trend is JJ Foodservice. Despite the tough climate, the Enfield-based wholesaler managed to grow overall sales during the calendar year 2020.

“While some businesses made large redundancies, we kept almost all of our team employed throughout the pandemic – it’s our greatest success story,” says head of operations Sedat Kaan Hendekli.

“We are currently investing in having the infrastructure in place to support our usual customers – and to anticipate changes in the market that may require us to take on more.”

Sadly, a number of national and regional foodservice players have been less able to mitigate the impact as successful and well-run customers have been brought to their knees through no fault of their own. When these are family-run businesses, the impact is more heartbreaking.

“It is ugly. It has been terrible. The good, the bad and the ugly. Retail will survive. But for a lot of weaker players in foodservice this will be a step too far now and they will fall,” predicts Tony Reynolds, MD of Reynolds Catering Supplies, which lost 95% of sales overnight at the start of the lockdown. “2019 was probably our best year. Our 2020 budget was looking even better. We’ve gone from hero to zero in 10 months.

“It’s hard to put that into words – the trials and tribulations we have been through. We’ve all had to make sacrifices. Our customers are on the edge now. A lot of businesses out there are in a perilous state and that will take months to filter through. Once everything can be opened it will be on a cliff edge – there are just so many things that aren’t good about that situation.”

That’s where the need for a joint effort has come in. The FWD has campaigned for months for sector-specific support. That’s happened in Scotland and Wales, where the devolved governments set up special funds for wholesalers in December. There, grants are already finding their way to operators. However, foodservice wholesalers in England have battled through the crisis thus far without any such support.

When asked why English wholesalers appear to be treated differently from public-facing hospitality businesses such as pubs and restaurants in different parts of the UK – and of course major grocery retailers, many of which were given business rates relief despite a Covid-19-driven sales windfall – government representatives invariably cited how wholesalers could access the furlough scheme and could apply to local authorities for special discretionary grants, which are available to any business.

Finally, last week prime minister Boris Johnson offered wholesalers in England some hope. As well as setting out the roadmap to get us all out of lockdown, he also singled out wholesalers suggesting more help would be forthcoming.

“I am acutely aware of the businesses that have fallen through the cracks,” he told Parliament. “Wholesalers, for instance, who find it difficult to qualify under one scheme or another. We are doing absolutely everything we can to make sure we give the support people want.”

But in this week’s Budget, foodservice wholesalers were once again left disappointed, as Chancellor Rishi Sunak made no mention of offering wholesalers specific relief, on the grounds that wholesalers are “reasonably accessible by visiting members of the public”, an HM Treasury spokesman explained to The Grocer.

Two new entries make Big 30 debuts

This year sees two new additions to the Big 30: Pricecheck and Holland Bazaar.

Sheffield-based Pricecheck was founded more than 40 years ago but after moving into health and beauty wholoesale, joint-MDs and brother and sister combo Mark Lythe and Debbie Harrison (pictured) have taken it into household and food and drinks, and expanded it through exports. Sales rose 20% to £98m in the year to 31 July 2020.

North London’s Holland Bazaar saw sales rise 12.1% to £93m for the year to 31 March 2020. Headquartered in Edmonton, the first Confex-member on our list is a family-run business. After starting out as a small fresh fruit & veg wholesaler, it opened its second depot in Croydon in 2017.

While wholesalers may be eligible for access to restart grants, the government is hugely reliant on the sector in supporting the retail, hospitality and leisure sector as the country opens up in the coming months. Even if it stays open for good this time, there’s no guarantee that wholesalers will survive.

No comments yet