The pandemic days of employers making strenuous efforts to support staff are over, as pay lags inflation and competition for roles increases. Instead, more sustainable – and cheaper – support is being offered

It’s been hard to grasp the scale of the changes to working life in recent years. Covid and its attendant lockdowns wrought huge upheaval for employers and employees alike, and now with the pandemic behind us, all parties are trying to piece together which elements should be embraced and which should be binned.

One of the key outcomes seemed to be an emboldened workforce. “When we looked at the numbers three years ago, we got feedback from employees saying: ‘I’m underpaid and undervalued.’ And employers were running around, saying: ‘Right, how do we reward and retain our great talent?’

“Well, three years on, they haven’t effectively done that. Actually, in some cases, total salary packages have gone down – surreptitiously. And there’s the key word,” says Steve Simmance, founder of fmcg recruitment specialist The Simmance Partnership. “Surreptitiously.”

“Hardship payments and working from home allowances have dissipated or disappeared”

Steve Simmance, founder of The Simmance Partnership

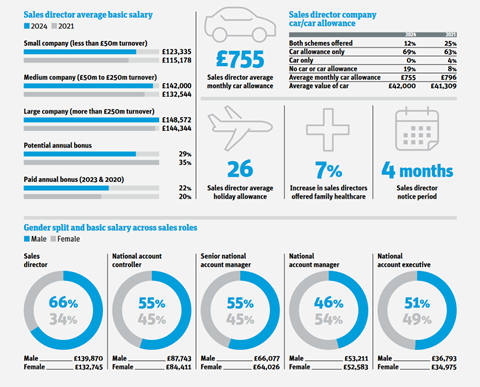

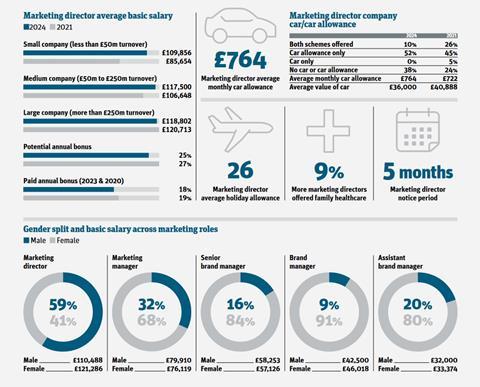

TSP’s latest salary guide, which analysed sales and marketing pay packages across 19 roles at over 300 fmcg suppliers, reveals that salaries have not moved on as much as expected in the past three years and certainly not as much as would be needed to combat inflation.

According to the guide’s data, from 2021 to 2024, sales salaries increased about 6.5% and marketing salaries by about 9%. In that time, the Retail Prices Index (RPI) has increased by 21%, The Simmance Partnership estimates. Something doesn’t add up.

That something is, of course, the cost of living crisis. If Covid was for many in grocery a boon, record inflation has meant people are buying and/or spending less, and the industry has lost sales hand over fist. Of the top 100 brands in The Grocer’s Britain’s Biggest Brands 2024 report, 71 reported volume declines. So, what does the salary and benefits landscape look like in a post-Covid world?

There is good news: the gender pay gap is narrowing. In 2021, it was 6% for sales roles and 19% for marketing roles. In the 2024 survey it was 5% and 1% respectively. “Women are earning the same and more in some marketing roles,” notes Simmance. And while there are disparities, “the good news is employers are working hard on diversity to address pay gaps throughout the chain of command”.

Another encouraging finding in the survey is the marked increase in pay for marketing roles. “Marketing has really caught up,” says Simmance. “Or is it the case that sales has been caught up? In sales we’ve seen a reduction in head counts and bonuses have dramatically dropped. But the marketing population are being paid a better dollar for a better day’s work. There is more focus towards branding, consumerism and share of voice, rather than the volume and value sales people are responsible for. Marketing has stepped up and become more important as brands need to work bloody hard across more areas. It used to be just ‘pile it high, sell it cheap’ and for the last 30 years that worked as food has been cheap. But those days are gone, there are no longer the same deals as before and as sales keep falling the marketing role gets harder.”

“People are prepared to reduce salary in the interests of a more flexible working relationship”

Steve Simmance, founder of The Simmance Partnership

But the jobs market for white collar workers in fmcg is tough. With huge swathes of senior and middle management ripped out in the wake of the cost of living crisis, recruitment is at a 30-year low, says Simmance, which means employees are becoming more conservative in their demands.

As well as depressed wage inflation, another casualty has been bonuses. “During the pandemic, bonuses were off the charts as revenue and profit performance shot up. But in the past two to three years, the combination of lower sales volumes and huge cost of goods increases has resulted in lower performance-based payouts. And potential bonuses are also lower. There’s just a realism about how tough the market is that the good times are well and truly over.”

As a result, says Simmance, the employee is coming to their senses and saying: ‘Actually, I don’t want to rock the boat here and ask for more money.’”

Richard Lim, CEO of Retail Economics, agrees. “I think you can see, from a simple commonsense point of view: the prospects of the economy look much weaker, interest rates are on the rise and people are paying more on their mortgages and rents,” he says. “So, all of a sudden job security becomes a lot more important. People are maybe a bit less willing to move around to different roles and take that risk and move on.”

Sales roles: salaries and benefits

Huge swing of the pendulum

What ultimately drives wages in fmcg is not just performance, but the balance between demand for and supply of talent. And right now, there is a huge swing of the pendulum towards an employer’s market. With too many sales and marketing people in fmcg, says Simmance, particularly at the top end, this is allowing employers to be more hard-nosed than a few years ago when it comes to salary and package negotiations.

Damian Clarke, chief sales officer at Henkell- Freixenet, says the wines and spirits supplier has raised salaries each year from 2021 to 2024 at a rate slightly behind inflation over the same period. “Our objective is to provide a competitive and motivating reward package, including salary,” he says. “To do this, we have to be mindful of the inflationary environment but not slavishly follow it.”

With less pushback from employees, Simmance has seen a change of focus in salary negotiations in which “the salary factor isn’t quite the burning issue at the moment you might expect. It’s also about lifestyle, quality of life, employee welfare, being cared for and nurtured by their employer. That’s what is starting to mean a lot, rather than how many more pounds you earned this year than last.

“There’s a dichotomy. Money is tight. It’s harder and harder to get by. The reality for many workers is: they don’t have enough in their pocket but they accept life is going to be tough and look to get the best benefits in kind.”

Different benefits

In 2020 and 2021, during the most testing periods of the pandemic, there was an explosion of soft benefits offered by companies aimed at attracting and retaining employees. Suddenly there were yoga and mixology classes on Zoom, ‘bring your dog to work’ days and more, especially among SMEs. Meanwhile, many companies also provided temporary hardship payments and working-from-home allowances.

According to Simmance, these have since “dissipated or disappeared” in favour of simpler, more sustainable benefits including purchasing extra holiday, improved healthcare packages and wellbeing or volunteer days.

“In a recent internal survey,” reveals Bryan Carroll, general manager at Oatly UK & Ireland, “95% of our team agreed with the statement: ‘Overall, working at Oatly is good for my wellbeing’, underscoring the value we place on our employee’s welfare.” He notes that Oatly has been offering private healthcare since before the pandemic, but since then it has provided “100% flexibility on working from home”, instituted a quarterly wellbeing budget that allows employees to “allocate funds toward their personal wellness pursuits” and added unlimited access to virtual or face-to-face therapy through Self Space.

“This was a significant investment in people’s mental health, but in a recent survey it was cited as the benefit that the team was the most grateful for, with three-quarters of them making use of the service at some point,” Carroll adds. “I think people are holding employers to account for looking after their health and wellbeing much more since the pandemic.”

“Employers have had it too good for too long, using lots of excuses to underpay”

Steve Simmance, founder of The Simmance Partnership

Simmance also notes the proliferation of benefits companies such as Perkbox, Reward Gateway and Edenred, which offer employees perks and discounts on items from tech, fashion and travel to cinema tickets and events. Edenred’s website promises to build “stronger connections with employees, customers, sales teams, and channel partners to drive higher engagement and performance”.

“Where employers are able to manage ‘the war on wages’ is to offer stuff to employees that, frankly, doesn’t cost a lot of money. Like a mental wellbeing first aider, charity days, purchasing extra holiday,” says Simmance. “That fundamentally doesn’t change the overhead budget dramatically compared to when you offer someone a 5% or 10% pay rise. If you do that across several hundred people, that changes your paradigm. So, I think employers are, in a stealth-like way, saying: ‘We’ll look after our employees, but we’ll do it in a fashion that doesn’t cost us that much money.’”

Another key finding of the salary guide is a reduction in car benefits. Previously, it was commonplace for those working in sales to receive a car or car allowance, whereas now an average of 53% of companies do not provide a car to their employees – a considerable increase from an average of 37% in 2021. Marketers are also losing out, with 69% of companies scrapping car benefits, compared with 52% in 2021.

While this may be due to the fact that many meetings are now held online, Simmance points out that employers “haven’t necessarily adjusted the base salary to make up for the difference. They’ve just taken the benefit away.”

Marketing roles: salaries and benefits

Read more:

-

Low Pay Commission to consult on national living wage rates

-

Asda confirms some workers may still be waiting for correct pay

-

Holland & Barrett latest retailer to boost staff pay

Hybrid and flexible working

Another key change wrought by the pandemic that links to pay is flexibility. Hybrid working and flexible hours are now an indelible part of employment negotiations for many functions in fmcg and beyond, and today 62% of companies now offer a two-day office, three-day home-based working week.

“Nearly every candidate will enquire about our approach to flexible working at some point in the hiring process,” says Carroll. “We only prescribe the whole team come together physically for a few key moments in the year. Our mantra, and expectation of those who work here, is that we are all adults who are capable of marrying how, when and where we do our best work. Our flexible working approach is often mentioned as one of the key reasons people love working here.”

Earlier this year, Asda confirmed it was experimenting with flexible working initiatives aimed at retaining store managers, including a 20-store trial of a “four-day working week for the same pay and benefits”. And while a widespread four-day week is a long way off, Lim says that “flexible working is a much more important variable in the overall package when people are considering who they want to work for and what kind of salary they expect”.

Attitudes to flexible working:

62%

of companies now offer a two-day office, three-day home-based working week

4%

of companies discourage hybrid working

Simmance agrees “we’re seeing that a lot. People are prepared to reduce their salary in the interests of a more flexible working relationship with their employer.” He cites recent conversations with two fmcg job candidates, one of whom was prepared to drop her salary by £10,000 to go from four days in her central London office to one, and another who works for a well-known tea brand on a remote contract and would like to be in the office occasionally, but “the minute she has to start travelling in, she’s going to ask for more money”.

He adds, though, that he’s now starting to see some of the bigger businesses, and also some smaller ones, take a harder line. “Three years ago, the tail was wagging the dog. Employees were saying: ‘This is what I want.’ Now the dog is starting to wag the tail again. How’s that going down? I can tell you it’s going down very badly.”

“People are holding employers to account for looking after their health and wellbeing”

Bryan Carroll, general manager at Oatly UK & Ireland

Carroll believes that handing out diktats is counterproductive. “For us, it’s simple: More flexible working structures retain talent. We will always operate from a place of trusting those who work here. In contrast, mandating all employees to be in the office five days a week is coming from a place of fear. Building rules and regulations for an entire workforce based on mistrust is not likely to attract or retain the best talent. The next generation simply won’t have it.”

Some have tackled this more constructively. Procter & Gamble, for example, expects employees to work three days a week at its HQ in Weybridge. But it invested heavily during lockdown in gym facilities and catering enhancements to make the office a more conducive environment.

Of course, as Simmance points out, having all the benefits and flexibility in the world “doesn’t pay your mortgage”. Many employees are “having a rough ride” financially. “Is that OK? I don’t think it is. Employers have had it too good for too long, underpaying people for the jobs they do and using lots of excuses to underpay. We’re way behind inflation on pay. That is evidenced. It was also evidenced three years ago, and we haven’t made an improvement. If we have it’s been marginal.

“This is always going to be a highly emotive subject for everyone, both employer and employee: Are we paying the right amount? Are we giving the right sort of benefits? You’ll never get the absolute silver bullet answer; you’ve got to be flexible.”

For a copy of the full survey see simmance.co.uk

No comments yet