This article is part of The Dairymen - our annual guide to the dairy industry that’s packed with insight and analysis on all the latest trends. To read the report, subscribe here.

To an outsider looking in, you’d be forgiven for thinking the industry just lurches from crisis to crisis,” says Arla UK MD and newly appointed chair of Dairy UK Ash Amirahmadi.

He’s not wrong. The past five years have seen the sector buffeted by challenges from farmer unrest over low prices, falling consumption and the rise of plant-based to concerns over the sector’s impact on climate change, not to mention Brexit uncertainty.

And then the pandemic struck. As the government imposed national lockdown on 23 March, a two-tier sector of haves and have-nots quickly emerged.

As we explain throughout this year’s Dairymen, those supplying the mults saw panic buying and a struggle to maintain supply. At the same time, suppliers exposed to the foodservice and hospitality channels experienced a dramatic slump in demand. More than a million litres of milk were poured down the drain in April, costing farmers more than £7m, while a host of cheesemakers were left with no market for their deteriorating product.

So how did the dairy industry respond to the shocks of the pandemic? And as further uncertainty looms, what shape is it in now?

Never has the dairy sector “seen such a period of change and uncertainty”, but it’s also shown “incredible resilience, adapting in the face of challenge” says Royal Association of British Dairy Farmers chairman Peter Alvis.

“The sector showed incredible resilience, adapting in the face of challenge”

“We have seen dairy businesses reinventing themselves almost overnight,” Alvis says, noting the speed at which some suppliers pivoted to DTC models or repurposed foodservice stock for retail.

Processors also had to act fast. The slump in foodservice demand caused by the lockdown “came at a time of peak milk production because cows were outside grazing the spring grass, meaning there was very little excess capacity in the system”, Alvis explains. This meant the reduction in sales through the foodservice sector had “a disproportionately large impact” and put extra pressure on the system.

Resilience

Preventing a flood of excess milk just as the spring flush arrived quickly became an urgent priority. The sector had to collaborate “in a way that really hadn’t been done before during my 16-year career”, says Amirahmadi. “At a very operational level, there was already a lot of collaboration and integration, in the form of milk collection, distribution and standards,” he adds.

But the sector had to come together at a more strategic level “when we approached that immediate drama of milk being poured down the drain”.

This required action on two fronts. To stop even more milk being poured away, farmers needed to slash production. At the same time, the industry had to stimulate retail demand.

First, the industry engaged with government through the food resilience industry forum and, after discussions with Defra, delivered a data-led analysis of the sector’s plight, driven by Dairy UK and AHDB, says Amirahmadi. What ultimately emerged was a £10,000 support package for the farmers worst affected by the lockdown, and the sector’s high-profile £1m Milk Your Moments marketing campaign, funded by industry, AHDB, Defra and the devolved administrations.

“I’m not aware of the government supporting any other industry like this,” adds Amirahmadi. “[Government] investment was only £500,000, but it was symbolic and made Dairy UK realise this is a much better way of influencing government.”

That investment paid dividends, with the campaign driving an estimated 11.2 million litres of additional liquid milk sales, worth £6.6m [Kantar 12 w/e 17 May].

“It was a brilliant example of industry and government pulling together during a crisis,” says AHDB dairy strategy director Paul Flanagan. “Every £1 spent on media turned into £13.99 of retail sales.”

“The Milk Your Moments campaign was a brilliant example of industry and government pulling together in a crisis”

On the production side, meanwhile, processors such as Müller called on their farmers to reduce output by 3% during April. That, of course, was easier said than done. As NFU dairy board chairman Michael Oakes said on numerous occasions this year, “you can’t furlough a cow”.

But thanks to the industry’s concerted efforts, year-on-year GB milk production was down by 75 million litres from April to June, says AHDB head of market specialists Chris Gooderham. This equated to a 1.6% drop in production in both April and May and a 1.1% drop in June.

The reduction was achieved primarily by removing cows from the herd and limiting yield growth by reducing feed rates. Without this “it would have put considerably more strain” on processing capacity and likely led to “significantly higher volumes of milk needing disposal”, he adds.

The sector has also been helped by wider lockdown eating and cooking trends. Dairy sales in the mults are flying, with shoppers making a beeline for cheese and butter in particular. Volume sales are up 10.7% and 11% respectively [Kantar 52 w/e 12 July]. This followed a 44% increase in scratch cooking and sandwich-making [IRI 12 w/e 25 April], points out Lactalis UK & Ireland group marketing director Heloise Le Norcy-Trott. “All of our brands grew during lockdown in line with the wider category,” she adds.

It’s a similar story from Saputo, which saw value sales of Cathedral City soar by 9.9% this year [Nielsen 52 w/e 5 September].

Ornua Foods UK MD Bill Hunter, meanwhile, says demand for Pilgrims Choice and its own-label cheeses peaked at about 20% higher than normal at the height of lockdown and is still about 15% higher now. “The key to meeting this surge in demand was the flexibility of our staff and proactively managing our relationships with the retailers,” he adds.

Indeed, close collaboration between processors and retailers was what allowed scores of dairy products originally destined for foodservice to be sold through the mults, preventing mountains of food waste and lost sales in the process.

Such joined-up working is here to stay, says Müller Milk & Ingredients CEO Jon Jenkins. “That better communication through necessity is going to become the norm, I hope. We now talk to customers far more frequently and candidly.”

“Dairy is still a very challenged sector. The margins are wafer-thin for farmers, processors and retailers”

At the same time, sizeable challenges remain. Milk prices continue to be volatile, dairy farmer numbers keep falling and there are big questions over the sector’s profitability. The UK’s six largest milk processors made a combined loss of £144m in the 2018 financial year. The soon-to-be-released 2019 results of many of those businesses are expected to make for further grim reading. “It’s still a very challenged sector. The margins are wafer-thin, for farmers, processors and retailers,” says Jenkins. “If you’ve got poorly invested infrastructure and an inefficient supply chain I think you’ve got problems.”

Questions also remain over the long-term future of mid-market players such as Freshways and Medina, who were both at the sharp end of lockdown losses and are long-rumoured to be set for a merger.

Fragility

And that was before further lockdowns were announced in the UK, with foodservice businesses in England this month forced to close again for four weeks. “The supply chain is still fragile and we’re still not out of the woods,” says Wyke Farms MD Rich Clothier. “No one knows how bad the second wave of the pandemic will be this winter. There is definitely more of a role for government to play here.

One way the government is set to play a bigger part is through the proposed reform of milk supply contracts, with Defra expected to publish its response to a recent consultation before the end of 2020.

Unfortunately, the proposal to introduce compulsory contracts has the potential to reopen divides that were largely bridged during the pandemic.

The NFU’s Oakes says the current “archaic” rules, based around a discretionary price model, are unfair and should be “torn up” due to the lack of protection they give farmers over milk pricing. Processors disagree, with Amirahmadi citing Dairy UK’s opposition to “any move which would end or impinge upon purchaser discretion” because it could lead to greater “instability, risk, and insecurity for farmers as well as processors”.

Despite these challenges, though, Amirahmadi believes the dairy sector could emerge from the pandemic in as good a shape as it has been in a number of years. He points to the success of added-value products such as filtered milk as a cause for optimism, and predicts there will be “significant” investment in the “value-up agenda”. “We’re doing it, as are others such as Graham’s and Crediton,” he adds.

He also sees UK dairy in a strong position post-Brexit. “Even if we do get a free trade deal with the EU there will continue to be some friction at the border, so that creates the conditions for investment in the sector,” he says.

“I see UK dairy being bigger. Of course, there will be a disruptive impact from Brexit, but I predict there will be a renewed confidence in experimentation and innovation.” After such a rollercoaster year for the sector, let’s hope he’s right.

How healthy are producers and processors?

Question marks over future processing capacity have long plagued the dairy sector. Industry experts Kite Consulting warned last year that a lack of investment had left liquid processors in a “precarious financial position” that could ultimately threaten the UK’s self-sufficiency.

That view was reinforced over the summer, when Kite director John Allen told The Grocer Medina Dairy’s pandemic-prompted decision to close its Watson’s Dairy plant in Hampshire would drive the liquid milk sector’s total capacity to under 100%.

But it’s the sector’s capacity to produce milk through its farmers that’s even more concerning, says NFU dairy board chairman Michael Oakes.

Producer numbers have been in decline for decades but fell by nearly 5% in the past year alone. This could ultimately put paid to any plans to increase UK self-sufficiency and put off potential investors, warns Oakes.

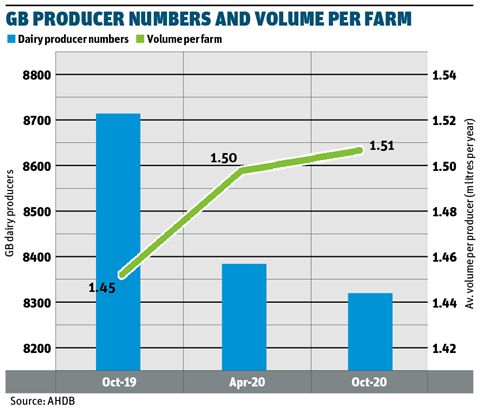

Milk volumes rose last year from an average volume of 1.45 million litres per year to 1.51 million, but AHDB data shows actual producer numbers fell 4.7%, from 8,720 last October to 8,310 in October 2020.

These figures may not be a “true reflection of the rate of farmers exiting the industry” due to time lags in collecting data, says AHDB, but the 8,310 figure represents a 19.8% fall on the number of dairy farms in Great Britain in April 2014.

The fall in producer numbers “reflects where farmers are in many cases” says Oakes. “We’ve had extreme milk price volatility at times over the past few years and that has put businesses under pressure.”

Financial difficulties have also hampered the sector’s efforts to recruit new blood, he adds. “Farmers get to a certain age and you can only take so much of just surviving.”

Price volatility reared its head again at the start of lockdown, when a host of processors cut their farmgate prices and delayed payments at short notice, pushing what was an average price in the region of 28ppl down to the 20ppl mark within days, while some reported the spot price falling below 10ppl.

“That’s why we need contract reform and innovation from processors in added-value dairy,” Oakes adds. “More fairness in the supply chain is key.

“If farmers keep leaving the sector we’ll ultimately end up importing more. That would continue the sector’s decline and that would be criminal.”

How the mults stepped up to the challenge

Tonnes of unwanted (and out-of-date) cheese being dumped. That was the very real prospect at the start of lockdown when demand from foodservice and hospitality operators collapsed overnight.

Stilton cheesemakers hit the headlines after warning their way of life was under threat due to a 30% fall in sales.

Other artisan cheesemakers said they were in an even worse position, with the Cornish Cheese Co among the most vocal in warning it had almost 20 million tones to shift in a matter of weeks.

Much of the excess was sold direct to consumer, but the major supermarkets also stepped up to the plate with a series of initiatives.

Tesco seized on a Jamie Oliver campaign to support two British farmhouse cheesemakers hit by the pandemic – Kirkham’s Lancashire Cheese and Keen’s Cheddar – by giving both businesses listings in almost 200 stores.

Booths also supported Kirkham’s and the wider artisan cheese category by ordering more products, giving them more promotion space in store, promoting the lineup online and selling more as pre-pack cheese.

But it was through emergency cheese boxes that the retailers arguably made the biggest impact. Aldi bought up four tonnes of surplus cheese in July, made up of the Cornish Cheese Co’s Cornish Blue, Fielding Cottage’s Norfolk Mardler, Shepherd’s Purse’s Yorkshire Blue and Bookham Harrison’s Sussex Charmer.

Waitrose made a similar move in May, when it launched its own ‘best of British’ box (pictured above), filled with five of its most popular British artisan cheeses: Westcombe Cheddar, Sussex Charmer, Yorkshire Blue, Cornish Yarg and Rosary Garlic & Herb Goat’s Cheese.

It came after a “drop in demand for the cheese counter which put orders at risk”, says Waitrose cheese buyer Alice Shrubsall. That’s why she decided to create the box and “stopped them from throwing their cheese in the bin”, she adds.

The boxes have been a huge success with shoppers, she points out. “We’ve sold more than 25,000 boxes since the end of June and we’ll be launching a Christmas version on 25 November.”

The move has also helped Waitrose strengthen its relationship with artisan cheesemakers, says Shrubsall.

“Shoppers love them, we have some loyal customers who have continued buying the box and keep coming back to ask when the next version of the box is out.”

No comments yet