Following the success of TfL’s junk food ad ban, over 80 local councils plan to follow suit. Could chocolate and cheeseburgers soon disappear from billboards forever?

When Transport for London (TfL) first introduced its ban on junk food ads in February 2019, the new rules weren’t exactly to everyone’s taste.

Critics called it absurd. Ineffective. A clear step towards a British nanny state. Some poked holes in a decision that could see pictures of gooey cheeseburgers banned across the transport network but pasted across billboards the minute you walked outside. Others warned of a £13m hole in TfL’s coffers if they dared to reject cash from some of the UK’s biggest advertisers.

And that was just their public response. Behind the scenes, criticism was even more vociferous. According to a Freedom of Information request by the University of Bath, large food companies and fast food operators requested informal meetings with policymakers to warn of the dire economic impact on small and vulnerable businesses. KFC offered its services to collaborate with the TfL taskforce itself, while the British Soft Drinks Association argued the policy should be abandoned due to a lack of academic research linking marketing and childhood obesity.

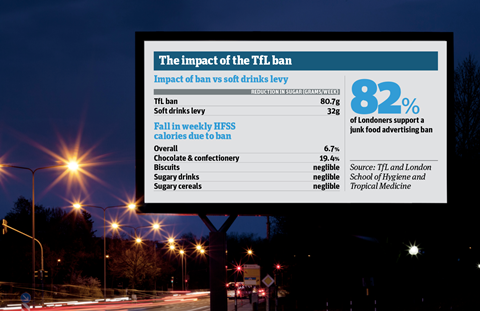

Three years later, though, and TfL will argue the results speak for themselves. The policy has triggered an average 6.7% cut in weekly calories from HFSS products and 19.4% fall from chocolate, a recent study by the London School of Hygiene and Medicine found. Meanwhile, sugar consumption fell by 81g a week – more than twice the amount achieved by the introduction of the soft drinks levy. The study argued the ban had “significantly decreased the average amount of calories purchased by households every week” from HFSS products.

These results are catching attention. A handful of local authorities have already followed TfL’s example, while at least 80 more are exploring the option.

In a way, it’s nothing new. For years, local authorities have sought to take greater action on HFSS advertising in their local areas, but felt they didn’t have the clout to push through change themselves, says Fran Bernhardt, children’s food campaign co-ordinator at Sustain, which is working with councils to put together the proposed bans.

Now, though, TfL’s move has “unlocked the ability for local authorities to do the same as there’s a precedent and a template for them to work from,” she says. “It’s a really exciting opportunity for local authorities and we’ve seen them show a great deal of interest.”

Five local authorities have now signed off on their own advertising ban: Bristol and four London boroughs (Southwark, Haringey, Greenwich and Merton).

Each has closely followed the template set out by TfL, which is a ban on all products classed as HFSS according to the government’s Nutrient Profiling Model. This includes all pre-packed food and drinks that are high in fat, salt or sugar, such as full-sugar soft drinks, chocolate, and breakfast cereals. Advertising must not include any references to HFSS products in visuals, text or graphics.

TfL has even gone beyond HFSS products. When a product is compliant but belongs to a category that largely falls foul of the rules – a low-sugar breakfast cereal, for example – it must carry clear labelling that differentiates it from the rest of the category.

TfL has applied the ban to all council-owned sites including public transport and roadside advertising like roundabouts and bus stops.

Each to their own

Not all councils will follow this model to the letter. Each one has employed tweaks here and there to set its own policy apart.

Under the TfL scheme, for example, companies have a right to appeal against the ban. Yet many other local authorities are now planning to instigate an outright ban with zero right to appeal.

It is indicative of a seeming direction of travel in which councils are gaining confidence to become increasingly proactive above and beyond the approach pioneered on London transport.

In Southwark, for example – which passed its policy just four months after TfL – it has broadened the ban to include other categories. The regulations will forbid advertising of alcohol products, low-alcohol alternatives, tobacco products, nudity, sexual messaging services, gambling and betting, as well as ads with ‘hateful or discriminatory content’.

The policy contributes to the “whole systems approach to promoting healthy weight that has been applied in the borough for a number of years,” says a spokeswoman for Southwark Council.

The scope of each council’s policy also varies considerably according to the scale of their own advertising estates. In some cases, only one or two sites may be owned by authorities, while in other cases – such as TfL – the physical estate is significant, spanning bus stops, billboards and council-owned buildings.

“The council is harming its own policy outcomes by hosting that advertising”

In Bristol, which became the first city outside London to sign off on an HFSS ad ban in March 2021, the policy spans 180 bus shelters and 17 hoardings, as well as numerous screens at venues such as museums, libraries and customer service points.

According to Carla Denyer, a green party councillor in the city and recently appointed co-leader of the Green Party of England and Wales, the “junk food advertising ban is a positive step because it reduces the pressure to consume unhealthy food but it doesn’t stop people doing so if they want to. It doesn’t reduce the availability of those foods.”

She argues the changes are a “logical” move for local authorities, who have been helping to boost demand for junk food by allowing advertising to appear on their property. “That’s working in direct opposition to the council’s own policies in other areas like public health,” Denyer points out.

“The council is harming its own policy outcomes by hosting that advertising. So I think it’s a rational choice that a lot of councils are making.”

In fact, Denyer is now among those who believe the policy must now be extended to other third-party sites – something that could be achieved by amending advertising policies in the city’s planning rules.

She’s not alone in her enthusiasm. More than 80 local authorities have approached Sustain for support in enacting their own junk food ad ban. As each additional one is signed off, the “momentum and excitement” grows, says Bernhardt at Sustain.

Read more:

-

Four HFSS layout trials underway in UK stores

-

Will HFSS laws shut down unhealthy innovation for good?

-

HFSS regulation is a challenge – but it offers fresh in-store opportunities for brands

-

Four solutions for retailers and brands ahead of HFSS regulations

-

How ready is the food industry for the HFSS clampdown?

-

HFSS brands need to mobilise public support to avoid tobacco-style controls

This excitement was accelerated by the publication of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine study in February. Local authorities “now have evidence of impact,” says Bernhardt. “Together with the template and the iterative process of the policies across other local authorities – as well as the evidence of the sustained advertising revenues – there’s a really strong case for authorities bringing these policies in.”

TfL has even shown local councils don’t have to miss out on any income as a result. Although it had prepared itself for a dent to advertising revenues, the first quarterly figures after the ban was instigated show the opposite effect. Revenue actually rose by 3% to £33m from April to June.

The news was compelling for “cash-strapped” local authorities, Denyer points out, and it was something she flagged to decision makers in Bristol.

For Susan Jebb, professor of diet and population health at the University of Oxford and recently appointed chair of the FSA, the accumulation of local authorities exploring such a ban is a welcome trend.

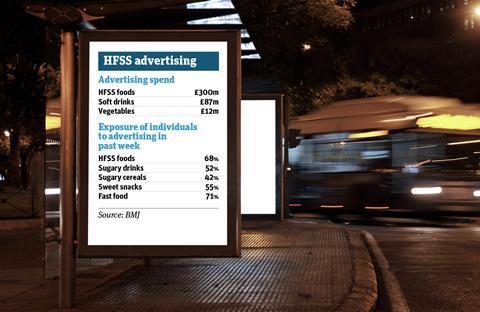

“Poor diets are the leading cause of avoidable ill health,” she says. “To support dietary change it’s important we take action to create healthier food environments. This includes reducing exposure to advertisements for less healthy foods since we have growing evidence that this encourages consumption.

“Ideally this would be national restrictions, but without this it is encouraging that some local authorities are taking action now to protect their local communities.”

Ads strike back

For many food and drink businesses already sweating about the HFSS laws due to arrive in October, the increasingly proactive approach of councils is a worrying and unwelcome burden, and in many cases viewed as pointless.

“Outdoor advertising bans are an easy, quick-headline option for local authorities but they are largely ineffective,” argues Tim Lumb, director of outdoor advertising specialist Outsmart. “Obesity is a serious and a complex issue and advertising has a positive role to play in tackling it. But it is not a silver bullet.”

He points out the outdoor advertising industry already restricts HFSS advertising voluntarily within 100m of any point along a school boundary and has done so since 2017.

“There is no substantive evidence that ad bans reduce obesity”

“This is a responsible and proportionate action for an advertising medium that in total accounts for only around 5% of the total advertising spend in the UK.”

It’s a view echoed by Sue Eustace, director of public affairs at the Advertising Association. “There is no substantive evidence that ad bans reduce obesity, in fact quite the opposite,” she says. “In Quebec, where no advertising to children, including food advertising, has been allowed since 1980, levels of obesity are equivalent to other parts of Canada.”

While there have been declining levels of junk food advertising on TV since 2008, obesity levels have continued to rise, she points out.

Preparation is key

However divisive these bans may be, the clear direction of travel is clear among local authorities. The only positive for affected brands is that further moves are unlikely to happen quickly.

Authorities are often forced to wait until contracts with advertisers and agencies are up for renewal before being able to enforce such a policy change. It’s why Bristol’s own policy has only recently started to take effect, despite being introduced more than a year ago.

That gives brands time to take the necessary steps to prepare for a wider clampdown. That could mean getting ahead and highlighting non-HFSS SKUs on outdoor adverts or diverting spend to less regulated channels such as radio or podcasts.

At the end of the day “the implication of this … is that we will be looking at a much more complex advertising landscape for HFSS brands,” says Elliott Millard, head of strategic planning at Wavemaker UK.

Another way for advertisers to work around these complexities is through campaigns that focus less on products and more on creative messaging. While the promotion of products will be banned, brand advertising will still be allowed so long as a non-HFSS product is still featured as part of it. McDonalds wouldn’t be able to advertise using just the their name, for example, they would need to include a non-HFSS item on their advert in order for it to be approved. It’s a crumb of comfort, says Millard, and could help trigger an ”extraordinary moment of creative freedom that comes from this regulatory constraint.”

Advertisers are wary though. In the long run, even ad characters could face a similar clampdown if campaigners are successful. At Adfree Cities, the end goal is to reduce outdoor advertising by all corporate brands in local communities as much as possible, says network director Charlotte Gage. “We think it’s something we haven’t consented to in public spaces and we’d like other things in those spaces instead, such as community noticeboards, local art or trees.”

HFSS is a great entry point for authorities to crack down on ads because people understand the concept of junk food and there’s been a growing conversation about it after the TfL move, she says. “People really get it when you say we shouldn’t be advertising a greasy McDonald’s near a school.”

Eventually, the hope is for local authorities to adopt more wide-ranging ethical advertising policies that cover the likes of high-carbon products too – a move that is already being explored by the likes of Norwich City Council.

“This is part of a bigger picture of trying to establish much healthier norms for children, for families and for everyone growing up in the UK,” concludes Sustain’s Bernhardt. “We want to be making sure we’re encouraging a shift to healthier foods and healthier lifestyles, and this is a big part of that.”

No comments yet