The Grocer blog: Daily Bread

What is junk food? Well, its grub that’s extremely calorific while providing little or no nutritional value, isn’t it? Like sweeties. And sugary pop. And tinned hot dogs. And takeaway pizza. And free-range eggs.

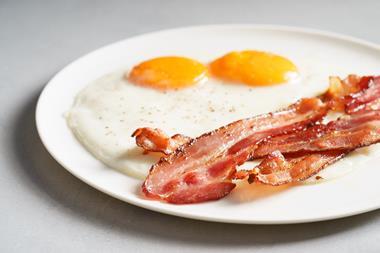

At least, that’s how TfL sees it – according to Farmdrop. The home delivery business, which specialises in farms and local producers, says its latest poster for the London Underground was rejected for showing free-range eggs, butter and bacon placed modestly amid an array of groceries.

‘We were told by TfL’s sales agent, Exterion, that these foods were not “high fat, sugar, and salt (HFSS) compliant”,’ Farmdrop wrote in its blog on Friday after having been forced to crop the offending trio from its ad.

‘Naturally, we were pretty shocked that a picture of some fresh groceries with a healthy mixture of fruits and vegetables, dairy, eggs and cupboard staples would flout TfL’s new junk food rules. But it turns out that TfL score foods individually according to a nutrient profiling model created by the government.’

That model, created by the FSA in 2004, uses a simple scoring system based on the nutrient content of 100g of a product. Points are awarded for ‘A’ nutrients (energy, satfat, sugar and salt) and for ‘C’ nutrients (fruit, vegetables & nut content, fibre and protein). ‘C’ is then subtracted from ‘A’ for a final tally. Foods that score four or above are classed as ‘less healthy’, as are drinks that score one or higher.

Read more: Salt levels in OOH children’s meals getting worse, says study

According to Farmdrop, the model is ‘a pretty crude measure and means that foods you would still think of as junk, like fizzy drinks with artificial sweeteners or low-fat fried foods, could in some scenarios comply with the new [TfL] regulations.’

TfL, however, insists it’s doing the right thing. “Child obesity in London is a serious issue,” a spokeswoman told The Grocer. “Almost 40% of children aged 10 and 11 are overweight or obese – one of the highest rates in Europe. This ban is designed to reduce children’s exposure to adverts for food and drink which could contribute to this problem.

“Our advertising policy requires brands to demonstrate that any food or drink products featured in advertisements running on our network are not high in fat, sugar and salt, unless they have been granted an exception. In this case, Farmdrop chose not to apply for an exception, and our advertising agent worked with them to amend the advertisement. We have never said that eggs do not comply with the policy.”

So, it was just the bacon and butter that were the problem, then? Sure, eating a lot of either is inadvisable, to say the least, but would one really call them junk?

And by the way, while childhood obesity is a very serious concern, you won’t see many kids chowing down on a block of butter on the walk home from school.

In depth: Will HFSS promotion bans lead to soaring business costs?

Most prefer crisps, candy and chocolate – the sort of HFSS snacks the ASA has come down hard on recently for targeting youngsters. Cadbury, Kinder Chewits and Squashies have all had their wrists slapped for contravening ASA rules based on that government nutrient profiling model.

The watchdog has done some good work. But it has also clearly demonstrated how the current characterisation of ‘junk’ can create inconsistency and confusion. The regulator was forced to reverse a decision to ban a Coco Pops ad, and it rejected complaints about a McDonald’s Happy Meal commercial because “80% of mains, 100% of sides and 64% of drink options available in the Happy Meal were non-HFSS products”.

Health secretary Matt Hancock is about to kick off a consultation on a TV watershed for junk food ads, the Telegraph reported at the weekend. The idea has been touted for years: when minister of state for public health in 2007, Dawn Primarolo felt obliged to allay fears the government was poised to introduce a pre-9pm ban on HFSS commercials.

So, it’s probably long past due now, and more likely than ever to become a reality. But before it does, we desperately need a clear and consistent definition of ‘junk food’ – preferably one suppliers, shoppers, retailers and regulators can all agree on.

No comments yet