Commodity price hikes, the war in Ukraine and inflation have changed the way Brits shop in the past year, while also piling pressure on suppliers and retailers. Which brands and categories have negotiated the system shock best?

In the first few weeks of 2022, a buoyant post-pandemic rebound seemed to be on the horizon. Overall UK retail sales had increased by 8.1% in January compared with 12 months earlier, reported the BRC, as consumers splashed out on home gadgets, furniture and fashion.

While grocery sales were more muted, with a 0.5% decline due to both a return to eating out and record high baselines from the midst of lockdowns, consumer confidence looked optimistic despite the quiet rumble of inflation in the background.

Then on 24 February, Russian troops launched their first missile strike on Ukraine. Within 24 hours, huge queues had formed at UK petrol stations as forecast fuel shortages and escalating prices spread panic.

By March, the cost of key food commodities, including wheat and vegetable oil, had spiked. One month later, growing pressure on global energy markets, coupled with a 54% increase in the energy price cap, saw households hit with soaring utility bills.

The shock immediately filtered through into spending habits, with total retail sales growth slowing to 6.7% in February before declining 0.4% in March and 1.7% in April. There was a brief respite during the long, hot summer, in which the Lionesses’ Euros 2022 win alone drove shoppers to spend £138m extra on food and drink, as they sat through the nail-biting final. But the emerging cost of living crisis only tightened its hold in the months that followed.

Indeed, September marked an inflection point as inflation soared, mortgage rates reached record highs, energy bills increased further and food inflation hit 14.6%, according to the Office for National Statistics. As a result, consumer confidence fell to record new lows, the GfK Consumer Confidence Index found.

It has, in other words been (yet another) rollercoaster year, packed with a few brief highs and plenty of crashing lows, just months after Covid loosened its grip.

So, what has that meant for UK grocery? Which categories have been worst hit and which – if any – have emerged as winners? And, with own-label sales growing, how can brands stay in focus as we head into 2023?

At first glance, the impact of the cost of living crisis on UK grocery looks surprisingly modest. Overall value sales fell 1.3% to £125bn in the past 12 months, according to NielsenIQ, with 54 of the 119 categories analysed even reporting moderate increases in value.

Dig deeper, though, and this incremental change belies huge volatility beneath. Not least the fact that total value sales dipped almost £2bn thanks to sharp average price rises across a number of categories as suppliers and retailers found themselves unable to bear the full brunt of inflation.

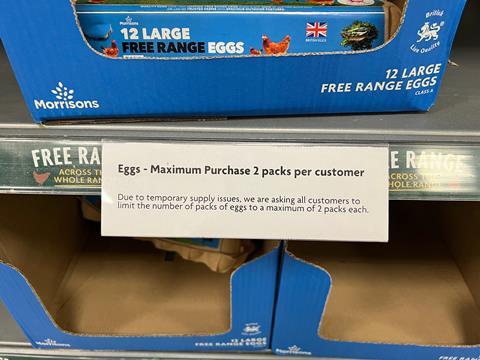

In fact, as of October, average annual grocery bills had jumped £643 (13.9%), according to Kantar Worldpanel, as substantial price increases were pushed through in the mults on meat, eggs and milk, followed by top household brands including Heinz, Alpro and Pampers.

This has forced Brits to get smarter about what they load into shopping trolleys. As a result, volume growth in the same period fell 7.1% as punters have sought out ways to cut costs – whether by splitting spend across multiple retailers to get the best deal, or shaking up product mix to avoid the worst of the price increases.

“While headline inflation may be 14%, shoppers are mitigating a lot of that by changing what they buy,” explains Mike Watkins, head of retailer & business insight at NielsenIQ. “About three to four per cent of inflation is being mitigated by shoppers trading down.”

In other words, don’t be fooled by the small value decline in overall grocery sales. Inflation is hiding a multitude of sins; consumers are buying significantly less in many categories.

“The analysis is showing, depending on the category, that if you put 10 products in your basket a year ago, you’re now putting 8.6 products in,” says Paul Martin, head of UK retail at KPMG. “You’re paying more because of inflation on those eight products, but you’re putting less in your basket.”

Trading places

Cost-cutting by consumers has taken two key forms in recent months: trading down to lower priced alternatives and trading out of categories altogether.

The former has seen shoppers reward brands that have been able to keep price rises to a minimum. In household facial tissues, for example, a 12.2% reduction in the average price of Cushelle fuelled a 48% increase in volume sales. At premium brand The Cheeky Panda, meanwhile, a 26.8% increase in the average price pushed volumes down by 9.8% in the same period.

Despite this hit to sales, price rises were unavoidable, insists Cheeky Panda CEO Julie Chen. “It is a mixture of significant energy and commodity price increases added to currency depreciations that are driving price increases,” she says.

“While The Cheeky Panda and many other firms have looked to absorb a lot of these price increases, the sheer volume of increases now means product price rises will become the new norm across most, if not all, categories over the next few months.” The brand is looking at ways to mitigate these price increases in any way it can, with in-store promotions and new SKUs planned for 2023. “[But] we understand that for many consumers, the continued price increases across every aspect of a household’s expenditure means they will look to make savings with their purchasing habits.”

Read more:

-

The top 10 biggest growing categories of 2022 by value

-

Five fastest growing products of 2022

-

The 10 fastest falling categories of 2022 by value

-

Five fastest falling products of 2022

That means, where they lack affordable brand alternatives, Brits are switching to private label.

Take bakery. Value sales of own-label supermarket loaves were up 9.1% while brands fell 1.3%. In canned beans, shoppers also flocked to own-label alternatives, with sales up 6.4% while brands fell 1.4%. Beans market leader Heinz saw sales tumble just £4.4m, despite its widely reported spat over price increases with Tesco. But the more telling number is the 13.8% volume decline.

All of which marks a reversal in fortunes. “Private label last year lost market share overall to brands as, during the pandemic, brands did better,” says Watkins. “This year, we knew private label would get back on track, and it has grown a lot quicker in the past six months due to the need to save money.”

Supermarkets have been adjusting ranges accordingly, increasing the size of value ranges for example, though overall, as we head in to 2023, private label ranges are down, while the number of branded SKUs is up. In those categories where affordable alternatives are hard to find, whether in branded or private label, or where products are regarded as non-essential, consumers are simply ditching items from their baskets altogether.

One such victim of this trend is butters, spreads & margarine. Despite a 12.9% increase in average prices, the category’s value fell 1.7%, falling to mitigate volumes by 38.9 million kilos.

Butter a luxury?

Capturing this dynamic at a brand level was leader Lurpak, with a 15.8% hike to average price shaving £18.6m off sales, as consumers refused to swallow such rich price increases.

Driven by rises in the cost of feed, fuel and fertiliser, brand owner Arla says it had little choice but to pass on some costs. “The cost of producing milk has increased to an all-time high and our farmers are struggling to cover their costs, which is resulting in less milk being produced,” says a spokeswoman.

“To balance this, we are absorbing as much of these costs as we possibly can, together with our retail customers and our farmers, to minimise the impact on consumers. Regrettably, the cost increases are so significant we do have to pass some of these on to ensure our farmers and our production facilities can continue the supply of products into the shops.”

It’s a similar story in canned meat and fish, where even inflation couldn’t mask a 9.7% decline in overall sales. Seven of the top 10 brands saw volumes fall. Market leader Princes, which lost £3.1m in the past 12 months, insists this is more indicative of anomalously high sales during the pandemic and a longer-term volume decline than any recent decision by consumers to swap canned goods out of their baskets, however.

“The trading environment is also a factor. Canned goods have suffered due to range rationalisation, meaning the size of the physical range is reduced in-store and therefore availability is limited,” says Jeremy Gibson, brand marketing director for Princes Group.

“Canned has always been very reliant on promotions, too, and the continued move towards everyday low prices has hindered volume sales to an extent.”

It’s a mix of challenges that he says the company is “actively combatting… through an ambitious commercial strategy, bold marketing activity and shopper-first innovation and new product development”.

That may be enough for Princes. But brands that risk being swapped for private label or ditched altogether have other options to appeal to cash-strapped Brits.

Economy versions

Brands could take note of strategies adopted during previous economic crises, suggests Bryan Roberts, global insight leader at IGD.

During the 2008 financial crash, for instance, the likes of Pampers and Duracell launched economy versions of their core brands, to maintain brand loyalty while offering greater affordability.

Already, it’s a mechanic that’s been deployed by the likes of Heck, which added a standalone value tier brand Yorkshire Sausage Co in August. By lowering the meat content in the pork sausages to 42% the brand has been able to support a price point of £2 for a 410g pack, 33% cheaper than its core lineup.

“The other mechanic is pack size, though that can be a double-edged sword,” adds Roberts. Offer large packs at low unit prices, such as 72 dishwasher tablets for £12, and brands risk appeasing more affluent shoppers with the capacity to spend up front, while alienating those with small or fixed sums to spend, he warns.

It’s perhaps why there’s a focus on smaller packs. “The biggest-selling SKUs in Poundland are 10 dishwasher tablets for a quid,” he says. “And Aldi has listed much smaller pack sizes of Ariel and Fairy detergent. That enables some shoppers to keep participating in the category or carry on buying that brand.”

Unit price and pack size aside, there is still merit in strong brand equity, argues Michelle Whelan, UK CEO at VMLY&R Commerce.

“Brands have always been vehicles for delivering value, be that convenience or product excellence or emotional reward,” she says.

“If you’ve spent years and millions defining what you stand for, don’t let hard times derail you. But you do need to find a lens that fits the moment.”

Consider framing promotional or marketing strategies that reflect current consumer concerns, she suggests, whether that “be through education – ‘family meals for under a fiver’ – enhanced loyalty schemes, supported by imaginative bundling, or by ratcheting up a ‘data for discounts’ proposition”.

Many of these strategies are already deployed by the multiples, at pains to prevent shoppers migrating to the discounters. Price locks on key items have been announced by the likes of Tesco and M&S, notes Roberts, while strong promotional discounts are being applied on fresh produce and protein as a direct way to combat the Aldi ‘Super 6’.

There’s been a renewed focus on loyalty schemes too, with Morrisons announcing in October that it would move many promotions behind its My Morrisons card as a way to add value to members.

Lipstick effect

For both brands and retailers the key will be a compelling enough proposition to convince consumers it’s worth the extra few quid. “What we’ll see from consumers is the balance between ‘do I need this?’ and ‘is it worth something?’” says Katrina Bishop, thought leadership activation manager at NielsenIQ. “It’s got to mean something to them to go into the basket as there won’t be those excess products that go in.”

Bear in mind there are still a proportion of consumers comfortably cushioned from the worst effects of the cost of living crisis, she points out. For these shoppers, elements such as brand equity and sustainability can still hold sway.

Many of these more cushioned shoppers will also be looking for affordable ways to indulge – another avenue that brands can explore. In fact, the so-called lipstick effect – in which consumers continue to splash out on small indulgences during a time of economic uncertainty – has already seen some fmcg categories emerge relatively unscathed from the tumult of the past 12 months. That includes, well, lipstick. Cosmetics saw volumes grow 16.5% in the past year, despite a 2.3% increase in average price. That’s not down to a few high-performing outliers driving overall performance, either (as can sometimes be the case). Each of the top 10 brands in the category recorded strong value and volume gains. (The end of lockdowns and the move to hybrid working doubtless played a part.)

A similar pattern played out in sugar confectionery, where brands saw a 9.2% increase in value and 4.5% rise in volumes, while cheaper private label SKUs fell 7.8% in units. This points to consumers willing to spend extra on small sweet treats from brands they’re familiar with.

“There will be lots of challenges in the market following the introduction of HFSS legislation and, of course, the cost of living crisis,” says Mark Roberts, marketing & trade marketing director at Perfetti Van Melle. “But confectionery is a resilient category that delivers little lifts and treats for consumers and loved ones, which won’t change. In tougher times, confectionery is an affordable, permissible treat.”

To leverage this, the Fruitella and Mentos supplier is investing heavily in marketing to keep its brands top of mind with key audiences, he adds, with Mentos Pure Fresh Gum sponsoring the Capital Summertime Ball.

“Confectionery is a resilient category that delivers little lifts and treats for consumers, which won’t change in tough times”

With many consumers also spending far less on eating out, there’s a similar opportunity for grocery brands to provide the indulgence of a restaurant meal with a more palatable price tag.

Where consumers did tuck into ready meals in the past year, for instance, they opted for premium brands over private label. That saw the likes of Charlie Bigham’s and Wasabi Home Bento helping to nudge up branded volume sales by 2.9% while own label fell 3.6%.

Worsening crisis

Whether small indulgences continue in the coming year remains to be seen, of course. But what’s almost certain is the cost of living crisis getting worse before it begins to ease – as many experts predict. Food inflation, in particular, is set to reach a peak of 17% to 19% in Q1 of 2023, according to IGD.

Kris Hamer, director of insight at the BRC, warns: “It’s going to get an awful lot harder for at least 12 months before it gets better, primarily from the perspective of mortgage rates for households and energy costs.” Already, there is “a huge amount of cost coming into the supply chain and retailers are doing everything they can to avoid passing on that cost”, he adds.

But as the situation worsens, there will be only so much businesses can do.

“The macroeconomic outlook for the year ahead remains very challenged, and consumer confidence is at its lowest point in 50 years,” says Matt Coode, partner at OC&C Strategy Consultants. “Consumer spend growth will be muted at best, and expectations for inflation remain high with forecasters predicting circa 6% CPI growth over the next 12 months. Interest rates are tipped to reach heights of 5% to 6% in 2023, which will further dampen spending power, especially for consumers with mortgages.”

In short, adds Martin, “next year will be worse than this year. If we have a cold winter and utilities increase further then we will be in for a very difficult Q1.”

Even once inflation eventually begins to slow, shoppers will still be grappling with like-for-like price increases that may be 20% higher than they paid two years ago, he says. “If we look at parallels in European history of inflationary driven downturns, it normally takes 18-24 months to come out.

“My advice to leaders in the sector is that this will still be with us way into 2024.”

It’s advice UK grocery bosses are unlikely to welcome. Not least as this record low consumer confidence will be compounded by a mix of longer-term systemic challenges and short-term shocks across their own supply chains too.

Coode says they’re “facing a perfect storm of operating challenges: chronic labour shortage, continued, albeit softening, supply-chain pressure, import duties making free trade harder and major financing issues creating a lack of capacity to invest.”

Not only that, “the outlook for energy inflation remains highly uncertain, as does the level of support offered to UK businesses to absorb this cost pressure beyond March next year.”

Never waste a crisis

There’s no easy solution. Each brand and retailer will need to juggle the pressure of inflationary costs on their bottom line with the risks to already fragile consumer loyalty of raising prices or adjusting pack sizes.

Ultimately though, it’s those brands that continue to invest, innovate and empathise with the shopper’s financial challenges that may emerge with their market share relatively intact.

“Never waste a crisis,” says Whelan. “If you want to stay relevant – or even become more so – you need to lean into what’s going on in the world. That’s not about over-claiming; there’s only a limited amount any brand can do. But people need a helping hand, and brands and retailers have the opportunity to step up and do their bit.”

Of that, there can be little doubt.

The Grocer Top Products Survey 2022: How can brands stay in focus?

Commodity price hikes, the war in Ukraine and inflation have changed the way Brits shop in the past year, while also piling pressure on suppliers and retailers. Which brands and categories have negotiated the system shock best?

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

The Grocer Top Products Survey 2022: How can brands stay in focus?

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

![Cheese ]GettyImages-664658023](https://www.thegrocer.co.uk/Pictures/80x50/1/8/6/282186_cheesegettyimages664658023_540979.jpg)

![Cheese ]GettyImages-664658023](https://dmrqkbkq8el9i.cloudfront.net/Pictures/80x50/1/8/6/282186_cheesegettyimages664658023_540979.jpg)

No comments yet