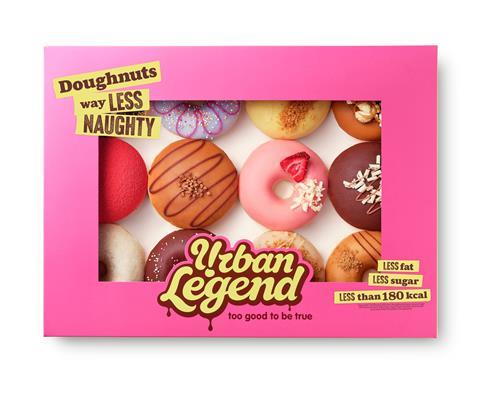

The doughnut brand’s tech is ingenious – and will be sold on. So why didn’t its products catch on?

Urban Legend’s collapse last week, as with any startup, should not come as the greatest shock. The company developed a world-leading technology for making ‘healthy’ doughnuts that drew £13m from investors including confectionery giant Mondelez. But its allure was always its position as a global forerunner – a recognition that while its technology was thrilling, it was a step into the unknown.

Arguably more important is what Urban Legend’s demise says about wider attempts to pioneer “healthy indulgence”. Low-sugar cookie startup Jnck Bakery also collapsed this month, Mars is struggling to sell its alternative Triple Treat bars, while Cadbury has axed its low-sugar chocolate completely.

Urban Legend is not short of admirers for what it achieved – a brand-new technology that cut half the fat and sugar from a doughnut by cooking the dough in steam and adding a micro-layer of fat to replicate the taste and texture of a deep fat fryer.

But taking on bakery was always going to be tough given the notorious expense of supplying fresh food to stores every day. Launched in 2021, Urban Legend clocked up over £11m in losses through its short life, mainly driven by the decision to follow rival Krispy Kreme’s model of personalised cabinets in stores, which require daily replenishment.

The cabinets are attractive for shoppers but inevitably mean higher prices, a factor that may have hurt Urban Legend given it spent most of its existence in a cost of living crisis.

“The business model creates a price premium which limits penetration, particularly at a time when consumers are more value-driven,” says Ben Scott, Krispy Kreme’s former head of growth and now founder of Elysium Consulting.

“Unless you hit real scale quickly, you risk sitting in a no-man’s land – too expensive for the mainstream and too under-resourced for niche.”

If Urban Legend therefore had more time to scale, perhaps it would have pulled it off. It was the collapse of a recent funding round that ultimately spelled its demise, but those inside the company insist sales were strong, with some stores selling £1,000 of doughnuts a week. “That’s a quite extraordinary rate of sale,” says one insider.

Notably, most of these sales were incremental, meaning Urban Legend was not cannibalising rivals like Krispy Kreme but finding a new market of customers previously avoiding indulgent foods altogether, the source claims.

Even more interesting for the Urban Legend team was that its doughnuts were most popular in the least affluent areas. “That’s not what you normally see in premium challenger brands,” the source says. “It’s because Urban Legend was designed in response to mass market health issues.”

The rise and fall of a legend

- July 2021: Urban Legend launches with its own store in Brighton. Four London stores are to follow over the coming year.

- October 2021: The brand secures £3m seed funding from venture capitalists, health charities and angel investors, with the money going toward a “cutting-edge test lab” to create products “indistinguishable from sugar-laden peers”.

- August 2022: Debuts in Tesco. Eight ring and five filled doughnuts roll into stores across London, after a trial in Putney and north Greenwich.

- March 2024: Samworth Brothers takes a minority stake, leading a £3m investment round through its venture capital arm Perfect Redd.

- October 2024: Mondelez International’s corporate venture capital arm SnackFutures Ventures takes a minority stake. Urban Legend founder Anthony Fletcher says it will help it accelerate on its journey towards “radical reformulation” in fresh bakery.

- 16 September 2025: The Grocer reveals Urban Legend is days from collapse, with more than 40 jobs at risk and a pre-pack administration expected within two weeks. The doughnuts are no longer available in Tesco and Sainsbury’s. It follows a recent failed funding round, according to City sources.

Not enough demand

Yet some outside the business cast doubt on its success in persuading shoppers to compromise their one-off indulgence for a supposed health benefit. Tessa Stuart ran in-store shopper research for Urban Legend several times as MD of Asset Research, and concluded there were simply not enough shoppers looking for a healthy doughnut to make it work.

“A lot of consumers employ a balancing act. ‘I eat healthily most of the time’ is the rationale, so when they have an occasional splurge, they want to go all in,” she says.

Jnck Bakery echoed the same message after it collapsed this month, noting it was unable to attract health-conscious shoppers to an aisle they now typically avoid. “Being a first-to-market concept in fresh bakery, as amazing as it was, was also our Achilles’ heel,” founder Alex Brassill told The Grocer.

The traditional doughnut is, of course, an ultimate indulgence product – a fat and sugar combination known to overcome even the strongest wills. Urban Legend’s attempt to replicate this without the health costs seemingly fell short for many shoppers.

Sean Field, founder of retail consultancy Beyond the Field, would often stop at Urban Legend’s doughnut cabinets while taking shoppers on “retail safaris” around supermarkets.

“They’d try it and enjoy it, but not enough to ever feel like they’d want a second one,” Field says. “Compare that to the Krispy Kreme experience where if there’s a dozen of them in front of you, you could easily eat the whole lot.”

Urban Legend deployed innovative marketing messages to stand out, placing cabinets next to Costa Coffee machines and uses phrases like “air-fried” before most people knew what one was. But its core health message ultimately landed on “low-calorie”, a move some commentators now see as misguided. “In the noughties that may have resonated. But times have changed, and people don’t want to be induced into guilt any more,” says Emily Tout, founder of high-protein dessert startup Mighty Slice.

Tout argues that shoppers instead want foods they believe are actively doing them good, often through protein or fibre. “If you’re going to ask consumers to sacrifice slightly on their experience, you’ve got to be giving them something for it.”

Yet rather than persuade, Urban Legend’s health claims often left shoppers suspicious. The trick with healthy indulgence is to show shoppers there’s no loss of taste, no loss of indulgence, yet somehow a magic trick has taken place that leads to fewer calories.

Stuart’s research for Urban Legend found consumers simply didn’t believe it. One of the reasons, she suggests, is that previous health pushes such as ‘low-fat’ often turned out to be a facade for high sugar content. “Shoppers said to me: ‘OK so these [doughnuts] are lower calorie. But what have they taken out and what have they put in?’”

That effort might be easier in other foods where shoppers are more willing to exercise healthy behaviour. Everyday staples such as cereal bars, crisps, and yoghurts, for example, have widely rolled out health claims with seemingly little blowback.

“Success comes where the product aligns with existing behaviour rather than trying to reinvent a deeply emotional treat like a doughnut or cookie,” says Scott at Elysium.

Read more:

-

Urban Legend prepares for collapse in blow to non-HFSS snacking

-

Urban Legend’s demise: self-fulfilling prophecy or cautionary tale?

The lesson of Urban Legend’s collapse is therefore not a signal that healthy snacking is faltering, Scott insists, but that the bar for execution is extremely high. “Challenger brands either need to overdeliver on taste or find foods that shoppers are already willing to compromise on,” he says.

Urban Legend undoubtedly achieved something remarkable – developing tech to cut health impacts of a fat-laden product in a way no other company has been able. The fact its patented process is to be sold to another major player proves there is value in what it pioneered.

But it is still early days in the development of new foods to help fight the obesity crisis. In many cases, the technology is simply not there. The battle is also immense in categories like confectionery where the incumbents are backed by some of the biggest and best marketing departments in the world. But perhaps, in time, Urban Legend will be seen as a pioneer that arrived marginally too soon.

2 Readers' comments